Teaching and Learning > DISCOURSE

Philosophy engines: technology and reading/ writing/ thinking philosophy

Author: Annamaria Carusi, Oxford e-Research Centre, University of Oxford

Journal Title: Discourse

ISSN: 2040-3674

ISSN-L:

Volume: 8

Number: 3

Return to vol. 8 no. 3 index page

The technologies and media available for carrying out the routine practices of research and study-the means for the ends of knowledge as specified in different domains-should, if efficient, recede to the background of practice. In particular, the means for carrying out the basic communications of a discipline should be sufficiently present to allow those communications to be carried out, but not one iota more. The pen between my fingers, the keyboard beneath them, the paper or screen on which I write should similarly be invisible servants. Even the voice which carries to a live seminar and discussion needs to be present but not too much: an extremely loud voice jars on the ear, makes listening a painful experience. Like Heidegger's hammer, it is when something goes wrong that these channels of communication obtrude in the communication and make themselves obvious.

Currently we are seeing the emergence of a number of new electronic and digital technologies in the communication domain, with strong claims being made regarding the way in which they are re-shaping research, education, publishing and other areas which are central to knowledge of all kinds (Borgman 2007). The single name given to these shifts is 'Internet'. The shift is most often denoted by the hyphenated 'e' in front of so many commonplace, traditional and familiar activities and domains (e-learning, e-finance, e-health, e-science, etc). Although this 'e' of electronic is not necessarily linked with online activity using Internet technologies, the dominant way whereby we come by our electronic content now is via the Internet-and that is where the real social, institutional and organisational shift is occurring. It is in the modes of exchange of content-of whatever form, be it a full facsimile version of an ancient and heretofore inaccessible document, or the ephemeral and light repartee of an email exchange-that the re-arrangement of the communications around knowledge is occurring, with longstanding and deep effects on knowledge institutions. The first of these changes occurs because once content is easily accessible and exchangeable in the way in which the Internet allows, it becomes desirable to do other things with it, and not only listen to, look at or read it. It becomes infinitely rearrangeable, recombinable, reconfigurable. When people communicate online, they often also share other electronic objects as well; and once these items are available online, in electronic form, they often want to do other things with them too: identify them (via tags, metadata and ontologies), point things out about them (via annotations or other means), or do more sophisticated analyses (abstract from them, render them in visual form if they are textual, or vice versa; generate and test hypotheses on the basis of them). In part this is in virtue of the nature of electronic content (for example, the facility of cut and paste, of change and manipulation); however, it is also due to the sheer quantity of content that can be found in even a modest Internet search which raises serious problems of analysis, interpretation and 'knowledge management'.

The medium for communication is easy (for many), not requiring any great knowledge in ICT, and none at all in computing. On the instrumental level, as a means to the ends of communication, it can be highly efficient. If the end is access to content, and if this is measured purely quantitatively, the Internet is now providing us with easier and faster access to more professional journals, information, and colleagues than ever before. How like the pen, and the associated technologies of 'hard text' with which were invoked at the beginning of this paper, is it actually? The answer is very much alike, but only because not even the pen is as modest or unobtrusive a technology for communication as its apparent disappearance from the phenomenology of communication makes it seem. As background to the points I make concerning the role of technologies in scholarship today, I shall discuss the crucial role of technologies for writing on shaping key features of philosophical discourse.

In this paper, I wish to consider how some of these technologies are affecting the teaching and learning of philosophy, as integral aspects of what it is to do philosophy, that is, its epistemic practices. By this I mean the means for the achievement of key epistemic goals of an area of enquiry, and the activities necessary for claims to be made and justified within a disciplinary area; what counts as 'playing the game'. Examples ranging from the natural sciences to the humanities are: dissecting, segmenting, relating, measuring, counting, comparing, classifying and categorising, defining, analysing, testing-by means of empirical test or 'thought experiment'; seeking counterexamples and counterfactuals, etc. From a sociological point of view:

An epistemic culture refers to 'those sets of practices, arrangements and mechanisms bound together by necessity, affinity and historical coincidence which, in a given area of professional expertise, make up how we know what we know. (Knorr-Cetina 2007: 363)

Taking the sociological point of view does not imply a commitment to a reduction of epistemology to sociology, or to any form of social constructivism. However, there is an interesting question to be posed regarding the extent to which an epistemic culture is shaped by the technologies available to it. If we are teaching philosophy using the new electronic means available to us, we cannot necessarily predict in advance that the practices we are teaching will remain unchanged by those means. This is a claim that I have already made elsewhere regarding argument (Carusi 2006), and which I wish to explore further in this paper.

Two perspectives on the relation between philosophical epistemic culture and technologies are explored:

- Philosophy and technology: this is the view that existing artefacts and other technologies provide a frame of thinking that makes some questions and solutions more obvious or intuitive than others.

- Philosophy in technology: this is the view that some technologies for producing / circulating discourse facilitate particular thinking, reasoning or interpretive processes more than others.

Often technologies play both of these roles, arguably discursive or communicational technologies in particular. I shall be anachronistic in the examples that I use to illustrate these different relationships, beginning with an example from Descartes and the camera obscura, reaching further back into the past to Plato's Allegory of the Cave and the Divided Line, and then forward to a current re-configuration of Plato's Cave.

1. Philosophy and technology: the epistemology engine

The first example I take from the philosophers Don Ihde and Evan Selinger. The term 'epistemology engine' is used by them to designate "a technology or a set of technologies that through use frequently become explicit models for describing how knowledge is produced' (Ihde & Selinger 2004:363). The use of the word 'engine' indicates the emphasis placed on doings and other practical activities as influencing the outcome of abstract or theoretical activity. As Ihde and Selinger put it: 'the metaphor of the epistemology engine suggests that through the praxis of these technologies, the energy of practical coping is converted into theoretical force' (Ihde & Selinger 2004: 363).

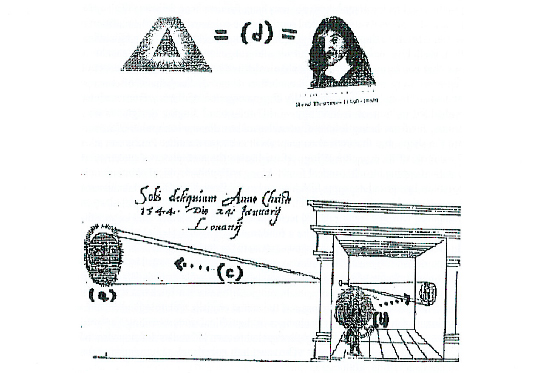

The example given by Ihde and Selinger is that of the camera obscura and its use-explicit and implicit-by both Locke and Descartes.

Their own description of the features of this system which make it an 'epistemology engine' is the best way of making the point:

We shall here generalize from this illustration of the camera and show how every important feature of early modern epistemology relates to the features of this epistemology engine: First, the sun (a), or "external reality" is outside the camera box and is not directly known to the "subject" (b), who is inside the box. Note that this distinction invents both the subject/object split and the notions of external and internal or subjective reality. Second, the subject inside the box knows only his or her ideas or impressions, that is, the image or representation on the screen or tabula rasa. Because this is the case, the subject must (c) infer via the geometrical method-which is the only relation between external and internal reality-what is the case. This, then, poses a major problem for early modern epistemology: How can the subject "know" that (c) there is a correspondence between external and internal reality? Descartes' answer lies in (d), his notion of a philosophical God or an ideal observer. The elaborate arguments about God, who would not, if perfect, deceive human subjects is supposed to guarantee the correspondence. But, as the camera model shows, the reason this is really possible is because the ideal observer can simultaneously see both inside and outside the box.

(Ihde & Selinger 2004: 365)

This is self-explanatory and as good an example as any of the way in which an available technology can shape-by explicit metaphor or in more underlying ways-an epistemological domain. There are several other examples, with current computational metaphors playing a very strong role. Recently computational modelling and simulation is beginning to emerge as a metaphor for shaping possible solutions to philosophical problems (see for example Barker 2002).

Let us try to project not the example as such, but the mode of thinking that it utilises, onto Plato and the Allegory of the Cave and the Divided Line1. For the sake of having a counterpoint with the example given by Ihde and Selinger, I too shall use an illustration, this time taken from an article discussing ways in which the allegory should be drawn so as to make its meaning clearer to students.

[image missing]

(Schonsheck 1990: 375)

Here too, there is a clear inside/outside distinction; there are appearances which are reflections of copies; copies or artificial objects; and reflections of real objects; and real objects. Explicitly, there is no technology referred to. However, the Allegory of the Cave and the Divided Line are structured analogously to an artifactual representational technology with which Plato was familiar, and in which his culture was steeped: the theatre, and all the technologies it involved, including the architectural disposition of space, and representational and communicative technologies2.

In the analogies of the cave and of the divided line we can see the influence of a complex human creation: theatrical representations. Let us begin with the cave. The theatrical structure of the scene within the cave is all too obvious and does not need to be stressed (the prisoners are like the audience of a theatre). What is more interesting is that in a drama like a Greek tragedy what is perceived is neither real nor is to be understood literally: this opens the way for a thought that revolves around the opposition between appearance and reality. It is worth remembering that the subject matter for Attic tragedies was mythology, not reality. This complex interplay between representation and reality emerges very clearly if we set up a stage by stage correspondence between the levels of knowledge in the cave myth and the layers of fiction in a Greek tragedy. The projection of artefacts on the cave wall corresponds to the fictional representation of a traditional myth (the fictional and representational value are further stressed by the use of stilts, masks and lavish costumes). The artefacts being carried behind the prisoners corresponds to myths (which are also human creations). Reflections of real objects outside the cave correspond to the symbolic meaning of the drama. Direct perceptions of real objects outside the cave correspond to the realisation that the story represented on stage is directly relevant to real, contemporary events (de te fabula narrattor). Finally, the vision of the sun corresponds to grasping the universal meaning of the story represented on stage.

If we consider the divided line we can again see an interesting analogy with the working of an attic tragedy. In the divided line we have two symmetrical relations (reflections: real objects = real objects: metaphysical principles) involving three terms. In an Attic tragedy we have a similar structure (representation: interpreter [chorus] = interpreter [spectator]: meaning). Just as in the divided line analogy real objects are present on both sides of the main division; in Attic tragedy the interpretive work is present on both sides of the divide between stage and public. This analogy is reinforced by the fact that in Greek tragedy not all the action is performed on stage: many events are only reported by the chorus. This is mirrored in the divided line analogy, which stresses that what is directly perceived (real objects) is not all that is there to be understood and hence that beyond real objects there are laws and principles.

In sum, the multi-layered interplay between representation and reality expressed in Plato's metaphysics and epistemology can be seen as shaped by the whole technological environment of the theatre, including its architectectural division of spaces and its organisation and arrangement as a representational artefact3.

Through these two examples, of the camera obscura and theatrical representation, we see the shaping force of technology on the content of philosophical thought: that is, the way in which problems and solutions are framed and structured by the implicit or explicit metaphors of these technologies.

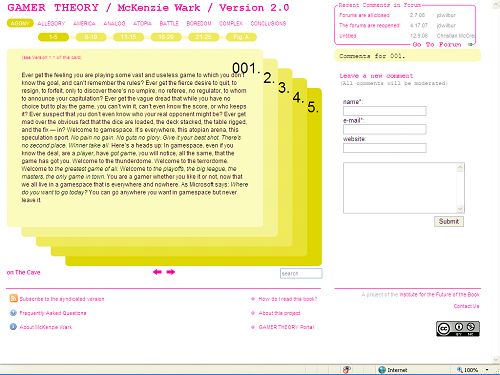

The next example follows Plato's Allegory of the Cave into contemporary intellectual life. Gamer Theory is a book by New Media scholar, McKenzie Wark, the web version of which is published by the Institute of the Future of the Book (2007). Increasingly books are published in both hard and electronic formats. The difference with this book is that it attempts to exploit the media features of Internet publication, with short segments of between a paragraph and a page in length, arranged in such a way that invites the reader not to follow a linear (beginning to end) sequence, while at the same time enabling them easily to locate the segment they are reading within the framework of the 'whole' book. This addresses the problem of readers losing their way around a hypertext and losing sight of the global context of local segments. A further new media feature is the open-ness of the text to comments by readers, with invitations to leave comments on the right hand margin4. The first section of Gamer Theory, titled 'Agony, On The Cave', looks like this:

http://www.futureofthebook.org/mckenziewark/gamertheory2.0/?cat=1

http://www.futureofthebook.org/mckenziewark/gamertheory2.0/?cat=1

The Allegory of the Cave is explicitly invoked and played upon. The stage setting paragraph occurs on the second 'page' of 'Agony' and reads thus:

Suppose there is a business in your neighborhood called The CaveTM. It offers, for an hourly fee, access to game consoles in a darkened room. Suppose it is part of a chain. The consoles form a local area network, and also link to other such networks elsewhere in the chain. Suppose you are a gamer in The Cave. You test your skills against other gamers. You have played in The Cave since childhood.* Your eyes see only the monitor before you. Your ears hear only through the headphones that encase them. Your hands clutch only the controller with which you blast away at the digital figures who shoot back at you on the screen. Here gamers see the images and hear the sounds and say to each other: "Why, these images are just shadows! These sounds are just echoes! The real world is out there somewhere." The existence of another, more real world of which The Cave provides mere copies is assumed, but nobody thinks much of it. Here reigns the wisdom of Playstation: Live in your world, play in ours. (Wark 2007:002)

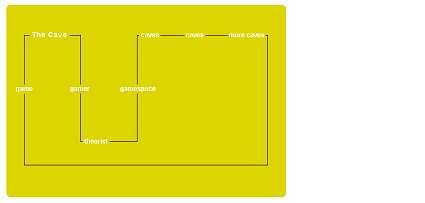

The Cave allegory is not merely translated into contemporary terms, but very different metaphysical and epistemological conclusions are drawn. The diagram that illustrates the cave is now rendered as follows:

Informed by gaming/ computing/ digital and algorithmic technologies, as well as by Plato's Cave, it is unsurprising that the conclusions about knowledge and reality are very different to Plato's own conclusions. At the intersection of these technologies, space and ontological realities are flattened out, there are no clear inside/outside spaces, or spheres of greater reality and firmer, more essential truths, and the only image of God-or ultimate reality-that offers itself is that of the computer geek, who 'implants in everything a hidden algorithm' (0.13). This 'flattened' space of interleaved and interwoven realities may offer itself more intuitively as a sensible response to metaphysical questions than it ever could to a Plato or to a Descartes. They may also seem shallow or at least contestable if not downright wrong by many contemporary philosophers. However, the point is rather the availability and intuitive plausibility of this metaphysical and epistemological outlook or mindset to many contemporary intellectuals, including, importantly, students. That this range of answers will be more readily available and seemingly obvious was predicted by Jean-Francois Lyotard in The Postmodern Condition (1979/1993). The particular example I have chosen is permeated by new media thinking; however other examples are not hard to find, in particular the pervasiveness of computational and informational framings of problems in philosophy of mind. Moral theory too has received its injection of computationally framed thinking in the form of Luciano Floridi's 'infoethics' (Floridi 2008).

The repertoire of 'engines' for philosophical thought is defined in part by the technologies and other artifacts that are available at different times. It is nothing new that technologies are used explicitly as analogies; the slightly different point made by Ihde and Selinger is that apart from being explicitly invoked, they also implicitly shape the knowledge domain, giving it a particular framing and structure. With McKenzie Wark's appropriation of the Cave, however, there is clear evidence of the role played by technologies as representational and expressive media as well as the general atmosphere of computational networked technology. With these we come to the second set of relations between philosophy and technology, that is, philosophy in technology.

2. Philosophy in technology: the philosophy engine.

'Philosophy engine' is an even more practical turn of Ihde and Selinger's metaphor: with this metaphor is suggested that the means that we use for carrying out the routine tasks of doing philosophy such as accessing material, reading and writing.

Philosophy is slow to change, and there are many who believe that in fact it remains fundamentally unchanged, at least with respect to the shape and nature of a specifically philosophical question. There has, however, been at least one major shift in the mode of philosophising: that is, from the oral-aural to the written mode. Even though our only access to the Socratic dialogues is in written form-and in fact, in a highly written form, one which is not simply the transcription of an actual dialogue, despite Plato's mistrust of the written-they attest to the existence of a way of doing philosophy which is conversational and spoken. These are Western philosophy's oral-aural roots: and with the spoken word-the very sound of speaking playing a not entirely insignificant role-sprung the essentially communal nature of this mode of doing philosophy. This way of doing things is always accompanied by a certain amount of disorderliness, something which is excised from Plato's Socratic dialogues, in the very act of transcribing them. Long preceded by different forms of literacy, the Gutenberg Press ensured the triumph of writing over speaking (at least in the Western tradition), culminating with the Cartesian meditation. With Descartes we have the beginning of Modern Philosophy, in its processes of argumentation as well as in the way in which his philosophy set the agenda for Western philosophical thinking for centuries to come. To what extent is it true that Cartesian philosophy-in its processes as well as in its substance-would not have been possible without writing? For writing and literacy generally allow for return and pause and so facilitate sustained reflection on a line of thought or argument; unlike oral discourse which facilitates and even requires accumulation and repetition, writing and literacy generally facilitate analysis and distinction. Freed from the pressure of live interaction, writing allows logic to triumph over mimesis (Dombrowski 1993: 118). And whereas its oral-aural predecessor had been noisily collective, this mode of doing philosophy is silent, private and solitary (Dombrowski 1993: 119). As writing provides the external trace for thought, dialogue is internalised, immediately self to self. It is not surprising that the practice of meditation, transformed by Descartes from a spiritual into a philosophical exercise, is itself rooted in writing, as described by Foucault5. While writing allows one to gain intimacy with one's self, it distances the other. To be lifted out of the need to communicate immediately with one's proximate others by means of the voice makes it conceivable that one's addressee is the universal other, of no particular time and place. And so too the conception of one's own self as universal, abstract, disembodied may be facilitated by at least not having to straightaway bump against the reality of the grain of the voice, the proximity of the body of one's interlocutors.

On the material level, writing as a means of doing philosophy also facilitated the view that a philosophical text is the expression of a single mind and outlook. Compared to the natural and social sciences, there are relatively few philosophical articles and books written by two people, and almost none written by more than two. Most often, in written philosophy, philosophers operate as individuals who are seen as expressing their thought, or, on the institutional level 'owning' it, their works being identified with them, with their names. The other side of writing as a philosophical process is of course reading and interpretation; and this activity is presumptively geared towards the notion of a text as the expression of an author's thoughts and ideas.

The material processes for doing philosophy-speaking, gesturing, writing in alphabetic or ideogrammatic form, or in any symbol system-have a deep effect on more abstract philosophical practices involved in thinking, reasoning, and understanding, and explaining, and it is in this sense that I have called them 'philosophy engines'. On one level, like epistemology engines, they make more easily available particular conceptions of the self in its relation to others; on the other, they engage and reinforce thinking and cognitive processes, such as syntactical rather than additive arrangements, analysis, formal reasoning, abstraction (Ong 1982; Carusi 2003:107) and other processes characteristic of formal discursive argument which have become synonymous with doing philosophy-or at least, modern Western philosophy. The oral form of African philosophy was, for example, often conceded only a folk-philosophical status6, precisely because it does not instantiate the same epistemic practices as are typical of philosophy in a literate culture.

Now let us take a look at what kind of philosophy engines the material processes involved in electronic media may turn out to be.

1. Philosophy has made plentiful use of Internet resources in a variety of ways, from the less adventurous to the more adventurous. It does not lag behind other disciplines either in communicating with colleagues online, nor in making texts available online and accessing them online. Full advantage has been taken of Internet resources for providing and gaining access to philosophical texts, and a student of philosophy now finds that she has an array of resources to make use of:

Electronic text is very different from the 'hard copy' (see how fast our terminology changes!) of the Meditations on First Philosophy of Descartes and his contemporaries, and even my own copy acquired as a first year philosophy student. While it is in textual written form, two features break the isolation of the single text: first, the ease of access to multiple texts of diverse forms (other scholarly texts, one's email, blog or Facebook page); and the simple device of keeping open multiple windows across which readers alternate and roam. Many of us do not like reading on a screen or online for this reason; we cleave to the ideal of the whole text that can be held in one's hands, 'all in one piece'. How fast reading practices are changing is a matter for empirical investigation; suffice to say that our own experience may not be the standard.

The phenomenology of reading online in typical cases is very different from that of reading hard copy linear text. The phenomenologist Wolfgang Iser gives an account of reading (hard copy) literary text (Iser 1978) which has many points of application to reading and interpreting (hard copy) philosophical text. In this account, the reader is described as occupying a wandering viewpoint within a text which is not given to her all at once. The reader brings to the text a horizon of expectations which are projected onto the text in the interpretive process. In a complex text, those expectations are most likely thwarted, producing gaps or indeterminacies in meaning. Hypotheses (guesses or hunches) are formulated as to how to close these gaps or render the meaning determinate, and these are projected onto other parts of the text, to see whether they are validated. This is not only a linear process as one is not compelled to go forward in a text as readers standardly also re-read, miss over parts, etc. For Iser this process tends to be a consistency building process, as in forming and testing hypotheses about meaning, we will try to build a semantic object (roughly, the meaningful object that corresponds to the physical text) that is cogent and does not contain contradictions. However, readers do this only if they expect that the physical text they are reading has a wholeness and integrity; that is, for example, that it issues 'from one mind', or that all the parts 'belong together'7.

However, one might add that in the absence of the expectation that the various viewpoints occupied by the wandering viewpoint do all 'belong' in one text there would be no reason to see them as being viewpoints of the same thing, and thus there would be no reason to try to connect them at all. For example, unless the reader of Adam Bede has reason to think that the complex range of viewpoints on this character all belong in that novel, and that he or she has not suddenly started reading another novel, this reader could not try to begin to connect them so as to construct that character and would not have any reason to do so.

This phenomenology of reading describes the process of forming hypotheses regarding the meaning of what one is reading at any point, projecting those hypotheses, and having them met or not; and through that process both assuming a text and semantic object; and producing (or at least co-producing) a semantic object. According to Iser, the consistency-seeking nature of this process is due as much to the way in which memory and cognition work, as to our cultural and experiential expectations of texts. It is not difficult to see how this phenomenology changes when skipping from window to window. Hypotheses formed are not constrained by the presumption of relating to but one text, as the boundaries between one text and another, one window and another, become blurred. It is because of this possibility of accessing numerous windows, each of which will contain a combination of text and other media used for different purposes-strictly scholarly, debate and discussion, entertainment and social networking, etc.-which results in meaning shifting as it migrates across these different windows and different contexts, a migration to which there is no obvious physical barrier. Texts merge; they mesh, they are 'mashed up'. A favourite current Internet activity is precisely the mash-up, which brings together digital objects (text, data, visuals, audio etc.) from many sources into one file.

This is not meant as a lament for the standards of yore, but rather to ask what will become of what we now know as philosophy when it is not intuitive to practitioners of philosophy that a text is the issue of one mind, and that to interpret is a consistency-building activity. That different practices of making sense (and making meaning) are engaged by electronic text and its concomitant applications is shown in the next section.

2. Texts-electronic versions of texts or increasingly texts that are 'born digital' -are the staple of philosophy; of its epistemic practices. Of course what is done with texts is very different in different traditions and styles of philosophy, as is what they are considered to be. Gaining electronic access to texts can be considered to be instrumentally good: more efficient, quicker, access to more. To more what? What scientists call data-but which perhaps we'll be happier to call ideas, concepts, claims, theories, etc. As with other forms of Internet use, both in the broad culture and in more scholarly or specialised pursuits, convenience does not stop at access, and soon there are other things to be done with texts. In fact, access alone necessitates other means of dealing with what is accessed because the form of access on the Internet is useful precisely because a simple search can render very large numbers of results, to which previously one would not have had access. But once one does have access to this large number of texts, one is then faced with the problem of how to process them. By a twist of irony, the advantage of Internet access is that it should deliver more to read on a particular topic, but delivers it in such quantities as to render it unreadable. Processing can no longer be accomplished by a single human mind or even, possibly by a collection of human minds-given the problems of getting them all to be processing in exactly the same way. Therefore, increasingly automated processing means are sought. Of these, I shall discuss two related processes with a bearing on reading text: text-mining and visualisations, and one process with a bearing on philosophical thinking: computational modelling.

2.1. Text mining: Once one has discovered the texts and other resources that one is after, there is the further question of what one does with one's 'horde'. Text mining is a computational process which operates on natural language documents in order to extract information that leads to the recognition of patterns or relations, often by means of a more or less elaborate algorithm and the intervention of computational linguistics. The results of mining are meant to show something about the body of texts mined that are either too time consuming for human reading or unavailable to human reading. The results are often associations, juxtapositions and patterns.

Text mining is now a standard humanities reading technology. At a very basic level, we have all done a form of text mining: any one who has done a search in a word document or a pdf document has 'text mined'. Text mining applications are generally based on word counts for empirical input and statistical analysis for processing. The most important analytical procedure is to pick out concomitant variations among frequencies of word use, which yields a grasp of patterns of use. What analytical procedure is used depends on the number of texts to be analysed and for what purpose8.

This kind of mining could be seen as greatly facilitating the process of forming, projecting and testing interpretive hypotheses that, if Iser is correct, is central to the phenomenology of reading [literary] texts. Its efficiency is based on breaking the temporal and spatial dependence of the 'wandering viewpoint' on the physical text. Instead of the wandering viewpoint being in the time and space of the text; waiting for it to give what the eye is searching for, a demand is made on the text to deliver. On the side of the text, one cannot but call to mind here Heidegger's notion of the 'standing reserve' except that here it is the text rather than nature which is being treated as a standing reserve on which we make demands. The algorithm intervenes between the reader's formation and testing of interpretive hypotheses and the text(s). This means, for the 'ordinary' reader, a point of opaqueness in the interpretation process.

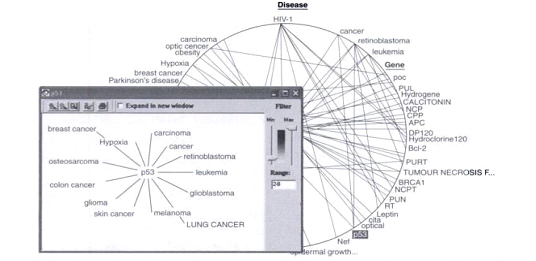

Be that as it may, this process ultimately changes, subtly or dramatically, the phenomenology of reading, the interaction with texts, and the kind of semantic entity that is produced. One way in which our experience of texts changes is by way of the results of the mining, which by their nature are more effectively rendered visually.

2.2. Visualisations:

The results of text mining are often rendered in visual form. Written language

is too, in so far as it is presented to the eye rather than the ear. It is

not sufficient to distinguish written from pictorial forms of visual presentations

by recourse to their conventionalised forms, since both are highly conventional.

Examples can show us the way.

Circle graph-based category connection map of medical literature relating to AIDS with inset of graphically driven refinement filter. (From Feldman, Regev, et al. 2003).

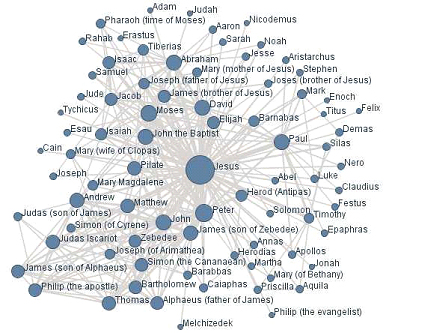

Visualisation of the New Testament based on network of figures mentioned together. http://www.dancohen.org/category/visualization

Visualisation of McKenzie Wark's Gamer Theory9.

Recall that one of the gains of literate culture is claimed to be the triumph of logic and the inception of the form of discursive argument characteristic of modern philosophy. It is noticeable that the visual rendering of this type of visualisation-which is not at all uncommon-is not logical, but associative. At the perceptual level, a relationship is established between entities / terms / concepts on the basis of their spatial contiguity, or some other qualitatively perceivable feature-for example, a larger node, or relationship represented by a line or other connecting symbol. The ability of the human visual system to make fine discriminations and apprehend patterns is here engaged. But what does it mean for the epistemic practices that this mode of acquiring information encourages? Shifting the sensorium toward the visual has been claimed by some to be the shift which allowed for the birth of modern philosophy (Dombrowski 1983), but not this pictorial form of the visual, which is associated more often than not with a peculiarly modern form of discursive illiteracy.

To what extent can philosophical problems be rendered visually? Rather the question needs to be framed as: what will a multi-modal philosophy be? None of these visual renderings of abstract relations and concepts stands alone, but is embedded within other discursive frameworks, We need to explore this world of multi-modality in order to be aware of how it works-so that we can be aware of some of the emerging features of new philosophies, perhaps practiced by our students who will be much more used to engaging with information in these ways. I shall discuss one last example of a computational means for processing and analysis, modelling, or the underside of visualisation.

2.3. Modelling

It must be recalled that beneath this apparently qualitative and 'analog' system of visual rendering, at least at the perceptual level, lie quantitative input and analysis. It is this combination of systems that is making a huge inroad in other arenas of scientific research. Computational visual means are at the heart of current scientific practice using super computing and grid technologies, and are changing disciplinary structures and boundaries: for example, the burgeoning field of computational biology is, through the means of modelling, simulations and visualisations, reconfiguring the domain of the life sciences. Through these computational resources the already blurred dividing lines between quantitative and qualitative methods in the sciences are once again being redrawn. An attempt has been made to harness these methods for philosophical ends. 'The Philosophical Computer' is the title of a book reporting on a project to discover the answer to the question whether modelling techniques are of any use to philosophy (Grim et al 1998). Among some of the examples are those which extend on familiar computational resources for logic (such as a model for 'graphing the dynamics of paradox') to those for problems in social and political philosophy. It is interesting that the creators of these models claim that they are 'heirs to a long tradition of philosophical modelling, extending from Plato's Cave and the Divided Line to models of social contracts and Rawls' original position', and that 'philosophical modelling is nothing new'. Perhaps it is just a particularly vivid way of doing thought experiments, and an extension of the human capacity to make alive to the mind the results of thought experiments.

An interesting difference between these visualisations and those of the texts that we looked at before is that the visualisations based on models require an understanding of the modelling process, including the algorithms used, whereas visualisations of the results of text-mining do not necessarily require an understanding of the algorithms. The thought experiment resides in the algorithm. The computational means for conducting the thought experiment can be philosophically demanding:

Our experience is that the environment of computer modelling often leads one to ask new questions or to ask old questions in new ways-questions about chaos within patterns of paradoxical reasoning or epistemic crises, for example, or Hobbesian questions asked within a spatialisation of game-theoretic strategies. Such an environment also enforces, unflinchingly and without compromise, the central philosophical desideratum of clarity: one is forced to construct theory in the form of fully explicit models, so detailed and complete that they can be programmed. With the astounding computational resources of contemporary machines, moreover, hidden and unexpected consequence of simple theories can become glaringly obvious. (Grim et al 1998: pp).

Are the philosophical virtues of clarity, rigour and explicitness aided by these astounding computational resources? This way of putting things makes it seem that there are not any shadowy or hidden corners of a problem, so long as you get it right, and that is, in programmable form. The philosophy engine here is precisely in the programmability of a thought experiment. It is this material constraint which gives shape and form to what can be hypothesised-and it is not one shared by Plato, or even a closer contemporary of ours, Rawls. Programmability is not at all a neutral constraint. Programming paradigms have assumptions built into them, which from the perspective of the uninitiated are either opaque, or not something with which they can engage at any meaningful level.

Underlying many of the tools used to find, organise, re-arrange, process and analyse electronic sources, there are most often algorithms. An algorithm is a recursive procedure, usually couched in formal-that is logical or mathematical-terms. Algorithms and algorithmic thought are pervasive in all aspects of computational techniques-including, first and foremost, the search engines which we use to find the sources of our information and intellectual engagement. What are some of the assumptions underlying algorithmic thinking? A team of computer scientists (Stepney et al: 2004) has listed some of the limiting assumptions of the algorithmic paradigm, and reasons why they are limiting, even for the purposes of computing, as follows:

- a program maps the initial input to the final output, ignoring the external world while it executes. Rather, many systems are ongoing adaptive processes, with inputs provided over time, whose values depend on interaction with the open unpredictable environment; identical inputs may provide different outputs, as the system learns and adapts to its history of interactions; there is no pre-specified endpoint.

- randomness is noise is bad: most computer science is deterministic. Rather, nature-inspired processes, in which randomness or chaos is essential, are known to work well.

- the computer can be switched on and off: computations are bounded in time, outside which the computer does not need to be active. Rather, the computer may engage in a continuous interactive dialogue, with users and other computers. 10

If this critique of the algorithmic paradigm is valid, we may say that the formal methods of computing and the formal methods of philosophy lend support one to the other, yielding the peculiar form of blindness that comes with excess of clarity.

3. Conclusion

It is, of course, not a given that these technologies will come to be fully absorbed into mainstream philosophy. Moreover, I have given only a very narrow selection of available resources, and have not even touched on the dizzying array of Web 2.0 applications which will no doubt make a significant difference to the interactivity of philosophical discourse11. Which tools and technologies do come to prevail depends on many different factors, including social, cultural and institutional factors. Time will tell. My point has been a different one:

The examples of computational technologies which could be viewed as potential 'philosophy engines' that I have given are meant to show how the mundane processes for accessing, organising, arranging and analysing electronic processes, even if not directly taken up for doing philosophy, could affect the epistemic practices of philosophy. The increase in the number of interpretational tasks relegated to computational resources combining Internet, analysis and interpretation tools and technologies will be powerful influences on the epistemic practices of intellectual endeavour generally, and are the epistemology and philosophy engines of the future. What account of intentionality, meaning and expressivity will be intuitive to practitioners of philosophy who use these technologies for accessing and analysing multiple electronic texts? What account of mind, self and morality will be intuitive to human readers grasping text content through the intermediary of machine readers? To what extent will the thoughts we can entertain about human and social rationality depend upon the material limitations of programmability? These are some of the questions that the new technologies post to philosophers. Finally then, when philosophers avail themselves of the great potential of e-learning, it is worthwhile also to cast a philosophical eye on the machinery that underlies it.

References

- Appiah, K. Anthony,' African Philosophy', in E. Craig (Ed.), Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. (London: Routledge, 1998). Retrieved June 03, 2008.

- Barker, John A. , 'Computer Modelling and the Fate of Folk Psychology', Metapsychology, vol 33, nos 1-2, (2002).

- Borgman, C.L., Scholarship in the Digital Age: Information, Infrastructure and the Internet. (MIT Press 2007).

- Burrows, 'Textual Analysis', in A Companion to Digital Humanities, S.Schreibman and R.Siemens (eds). (Oxford: Blackwell, 2004).

- Carusi, A., 'Taking Philosophical Dialogue Online', Discourse, vol. 3, no. 1, (Autumn 2003).

- Carusi, A., ''Perplexities of Teaching Philosophy Online', Discourse, vol. 5, no. 2, (Spring 2006).

- Carusi, A., 'Textual Practitioners: a Comparison of Hypertext Theory and Phenomenology of Reading for the Design of Online Reading Environments', Arts and Humanities in Higher Education, vol. 5, no. 2 (2006).

- Dombrowski, Daniel A. 'The Shifting Sensorium and Education for Literacy', in Teaching Philosophy, vol.6, pp. 117-126 (2003).

- Feldman, R & Sanger, J. (2007) The text mining handbook: Advanced approaches in analyzing unstructured data. Cambridge University Press.

- Floridi, L. (2008) Information Ethics, its Nature and Scope, Moral Philosophy and Information Technology, Jeroen van den Hoven and John Weckert (eds). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 40-65.

- Grim, P., Mar, G., & St Denis, P. (1998) The Philosophical Computer: Exploratory Essays in Philosophical Computer Modelling. MIT Press

- Havelock, E.A. (1982) Preface to Plato. Harvard University Press.

- Ihde, D & Selinger, E. (2004) Merleau-Ponty and Epistemology Engines. Human Studies, vol 27, p. 361-376.

- Iser, W., The Act of Reading: A Theory of Aesthetic Response, (Baltimore: John Hopkins Press, 1978).

- Knorr-Cetina, K. (2007). "Culture in global knowledge societies: knowledge cultures and epistemic cultures." Interdisciplinary Science Reviews 32(4): 361-375.

- Lyotard, Jean-Francois. (1979/ 1993). The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge. (Translation from the French by Geoff Bennington and Brian Massumi) Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Martin, L.H. et al (1988) Technologies of the Self: A Seminar with Michel Foucault. London: Tavistock. pp.16-49.

- McCarty, Willard (2004) Modelling: A study in words and meanings. In A companion to Digital Humanities, eds. S.Schreiberman, R.Siemens and J.Unsworth. Oxford: Blackwell.

- McKenzie Wark 2007 Gamer Theory. Harvard University Press. Web version: The Institute for the Future of the Book. http://www.futureofthebook.org/mckenziewark/

- Ong, Walter (1982) Orality and Literacy: The Technologising of the Word. London & New York: Routledge.

- Penny, Simon (2008) 'Experience and abstraction: the arts and the logic of machines, fibreculture, no 11.

- Schonsheck, Jonathan (1990) Drawing the Cave and Teaching the Divided Line. Teaching Philosophy, vol 13, no 4, p.373-377.

- Stepney et al (2004) Journeys in Non-Classical Computing. Working paper, May 2004. http://www.nesc.ac.uk/esi/events/Grand_Challenges/proposals/stepney.pdf

Endnotes

- I am deeply indebted to Giovanni De Grandis for discussions on this section.

- In Plato's terms, techné included poetry.

- There is far more to be said about the multiple levels of techné / technology in these myths and their role in Plato's metaphysics and epistemology which cannot be included here. See also Havelock (1982) for an account of how writing and representational media were influential in shaping Plato's thought.

- As well as the concomitant abuse of this facility that regularly occurs on the Internet, and the announcemnt that 'all forums are now closed'. Comments and other forms of interactivity require institutional arrangments in order to function; this institutional aspect is another space where there is a confrontation between traditional and 'e-' knowledge structures.

- Eg 'By the Hellenistic age, writing prevailed, and real dialectic passed to correspondence. Taking care of oneself became linked to constant writing activity. The self is something to write about, a theme or object (subject) of writing activity. That is not a modern trait born of the Reformation or of Romanticism; it is one of the most ancient Western traditions. It was well established and deeply rooted when Augustine started his Confessions. Martin, L.H. et al (1988).

- Eg by Appiah (1998).

- For a fuller account see Carusi 2006.

- See John Burrows, 'Textual Analysis' 2004

- I was also surprised by things that clustered together: 'theory' is close to 'entertainment', 'life' with 'world' and 'topology' with 'space'. The last of these three is to be expected, but the others are not. So for me what would be interesting would be to tease out the meaning of these spatial overlaps, and see if there are unexplored conceptual overlaps. That is one way I would use it in the writing process. The term 'lifeworld' has a particular theoretical meaning. But I did not use the term in the book. But maybe the concept crept in anyway, without my really wanting it to.' McKenzie, comments on TextArc

- See also McCarty (2004) and Penny (2008).

- However, it does need to be said that Wikipedia, one of the Web 2.0 phenomena which academics most love to hate, and which it is claimed will have a deep effect on what our Internet culture's conception of what knowledge is, is as much influenced by philosophy as future philosophy will be influenced by it: an excellent example of co-shaping. Larry Stanger, it's founder, is a philosopher, with a doctoral dissertation on epistemology titled 'Epistemic Circularity'. See Sanger, 'Who Says We Know? On the New Politics of Knowledge', and responses by other philosophers: http://www.edge.org/3rd_culture/sanger07/sanger07_index.html.

Return to vol. 8 no. 3 index page

This page was originally on the website of The Subject Centre for Philosophical and Religious Studies. It was transfered here following the closure of the Subject Centre at the end of 2011.