Teaching and Learning > DISCOURSE

Web-based Exercises and Benchmarked Skills A report on the mini-project 'Creating Web-based Exercises for Theology and Religious Studies Students'

Author: Rob Gleave

Journal Title: Discourse

ISSN: 2040-3674

ISSN-L: 1741-4164

Volume: 5

Number: 1

Start page: 29

End page: 49

Return to vol. 5 no. 1 index page

Introduction: Benchmarking Skills

Within the Subject Benchmark Statement for Theology and Religious Studies (TRS), published by the Quality Assurance Agency in 2000, there is a list of elements of knowledge and understanding, subject-specific skills and key skills which graduates in degrees in TRS are expected to have acquired during their degree programme. The QAA describes Subject Benchmarks as follows:

Subject benchmark statements set out expectations about standards of degrees in a range of subject areas. They describe what gives a discipline its coherence and identity, and define what can be expected of a graduate in terms of the techniques and skills needed to develop understanding in the subject.1

The statements 'represent general expectations about the standards for the award of qualifications at a given level and articulate the attributes and capabilities that those possessing such qualifications should be able to demonstrate.'2 No serious attempt has yet been made to measure specific degree programmes against these Statements by bodies external to the award-giving institution. In Subject Review, reviewers were permitted to measure programmes against the Statements only if the department under review explicitly referred to the statement in their Self-Evaluation Document. The Benchmark Statements are to be revised. Revisions were timetabled ('In due course, but not before July 2003, the statement will be revised')3, but at the time of writing nothing, to my knowledge, has yet been initiated. Therefore, we may (or may not) be getting new statements in the future.

In the TRS Statement, the level of skill attainment is divided into 'threshold' and 'focal'. The difference between threshold and focal skill attainment is rather like the difference between (my own team) Crewe Alex and Arsenal. Both play football, but Arsenal does it better. For example, students on a programme which offers only a 'threshold' level should:

Be able to summarise, represent and interpret a range of both primary and secondary sources including materials from different disciplines. 4

Students on a programme which offers a 'focal' level should be able to do this, but also: Be able to evaluate and critically analyse a diversity of primary and secondary sources, including materials from different disciplines.5

The difference is between those who can only 'summarise, represent and interpret' and those who can 'evaluate and critically analyse' these materials (ignoring split infinitives), and these materials constitute a 'range' (for 'threshold') and a 'diversity' (for 'focal').

Now, it seems obvious to me that any teacher of TRS in higher education will want his or her modules, units and programme to conform to the 'focal' level. Who wants to play for the Railwaymen, when you could play for the Gunners?

Unlike with Subject Review, where we all set our own 'Aims and Objectives', benchmarking aims to set universal standards against which we may all be tested. With Subject Review, a department which aimed low and achieved low could get 24 (not that we ever added up the scores, of course). Benchmarking is supposed to plug this loophole and maintain quality through national, agreed standards. Quality assurance has moved on since the Benchmark Statements were written, and we now have Institutional Audit. Time will tell how the Benchmark Statements will fit into this new 'light touch', though there are regular references to Benchmark Statements in Institutional Audit reports.

Whether one likes the TRS Benchmark Statement or not, it seems clear that it (or something like it) will remain one of the quality criteria against which programmes of TRS are measured. Who will do the measuring and how they will interpret the document may change over time, but there will be a document. Interpretation (as all scholars of religious texts know) is crucial: my 'critical analysis' may be your mere 'summary and representation'. The current Statement may be updated, and its content may be altered, but the principle that there should be a 'Benchmark Statement' and that TRS degrees (and TRS components of degrees) should be measured against it is not (it seems) open to question. In my view, it is highly unlikely that any future UK government will abandon the idea of nationally agreed standards in knowledge, understanding and skills. Ditching the principle of benchmarking would be seen as an unacceptable loss of public accountability within the sector.

Fortunately, the drafters of the TRS Benchmark Statement have devised a document which is sufficiently 'flexible' (some might say 'vague') to be applied to a large number of different programmes, and is not prescriptive in terms of the structure of a TRS degree. This was a wise move-it enables the community of TRS teachers in HE to define how they want the subject to develop, and it will hopefully ensure the continued existence of distinctive TRS degree programmes around the country. We will continue to play different games. Some will play biblical studies and Christian theology; some world religions. Some will see religion as a generic category, and only later divide study into specific traditions; others will see traditions as central and view generalising categories with suspicion. This is fine for subject-specific knowledge. The story may be different in terms of subject-specific and key skills. Here there will undoubtedly be a call for more uniformity. An employer will want to know that a 2.1 TRS graduate from university X will have better 'skills attainment' than a 2.2 TRS graduate from university Y, even if the Y graduate 'knows' more about Sikhism or Christianity or whatever.

With these observations in mind, I applied for, and received, a mini-project grant from the PRS-LTSN6 to devise web-based learning exercises and report on their success in developing key skills. The project was entitled 'Creating Web-based Exercises for Theology and Religious Studies Students'. During the completion of these exercises, students would hopefully develop some of the skills outlined in the Benchmark Statement. The aim of the project was not simply to enable conformity with the Benchmark Statement. It would, of course, be useful for a department under review to point to exercises like these when asked by a review team, 'How and where do you teach the skills laid out in the Benchmark Statement?' This is, if you like, one advantage of formalising skill attainment through setting specific exercises (whether web-based or not). The broader aim was, however, to find ways in which the skills outlined in the Statement could be integrated more explicitly into the curriculum. I do not consider the skills themselves to be contentious. I cannot imagine any modern TRS teacher saying 'Well, actually I do NOT want my students to be able to evaluate and critically analyse a diversity of primary and secondary sources. I want them to accept everything they read at face value (particularly if it is my own work) and read only one type of source.' In politically incorrect terms, the skills are motherhood and apple pie.

The 'benchmark' skills which the exercises were designed to develop (and in a formative manner, assess) are set out in the table below.

| Table: Target skills for the mini-project 'Creating Web-based Exercises for Theology and Religious Studies Students'7 | ||

| Skill No. | Threshold | Focal |

| In 'Knowledge and Understanding' | ||

| 1.8 | Be able to summarise, represent and interpret a range of both primary and secondary sources including materials from different disciplines. | Be able to evaluate and critically analyse a diversity of primary and secondary sources, including materials from different disciplines. 9 |

| In 'Discipline Specific and Intellectual Skills' | ||

| 2. | Be able to represent views other than the student's own with fairness and integrity and as appropriate express their own identity without denigration of others. | Be able to represent views other than the student's own sensitively and intelligently with fairness and integrity, while as appropriate expressing their own identity without denigration of others, through critical engagement in a spirit of generosity, openness and empathy. |

| In 'Key Skills (transferable skills)' | ||

| 3. | Be able to communicate information, ideas, arguments, principles and theories by a variety of means. | Be able to communicate information, ideas, arguments, principles, theories, and develop an argument by a variety of means... which are clearly and effectively organised and presented. |

| 4. | Be able to identify, gather and discuss primary data and source material, whether through textual studies or fieldwork. | Be able to identify, gather, and analyse primary data and source material, whether through textual studies or fieldwork. |

| 5. | Be able to attend to, reproduce accurately and reflect on the ideas and arguments of others. | Be able to attend to, reproduce accurately, reflect on and interact with the ideas and arguments of others. |

| 6. | Be able to use IT and computer skills for data capture, to identify source material and support research and presentations. | Be able to use IT and computer skills for data capture, to identify appropriate source material, support research, and enhance presentations. |

With this aim in mind, I set about designing web-based exercises; I then set them as tasks for my students as elements of the formative assessment in specific units.10 The rest of this paper is a reflection on my experience using these exercises. There is no quantitative analysis of questionnaires. Rather, I have opted to give summaries of the students' comments during feedback sessions after completing the exercises.

The Web-based Exercises

Since I teach Islamic Studies, most of the exercises I designed revolved around material related to that subject. The exercises can be found through the links on the gateway page I set up for students doing my units: www.bris.ac.uk/depts/THRS/IS.Webexgate.htm. They are not particularly sophisticated exercises. I am not a particularly sophisticated web designer.11 I, with my limited abilities in web design, did have one advantage for the project over a professional designer-my labour was cheap. The exercises were employed in a 'blended' learning environment, combining IT usage with classroom time.12

The exercises divide into three main types:

- Explicit skills training exercises

- Research and evaluation exercises

- Comprehension exercises

Some of the exercises include elements of all three characteristics.

1. Explicit skills training exercises

These exercises are comprised mainly of PowerPoint tutorials, made available through the Web. The students could complete these tutorials in their own time. No work was submitted, but by placing the tutorial on a Virtual Learning Environment site (in this case Blackboard), I could check which students had completed the tutorials and which had not. Blackboard records which students view particular elements and sections of the site as the students have given their username when accessing the site.

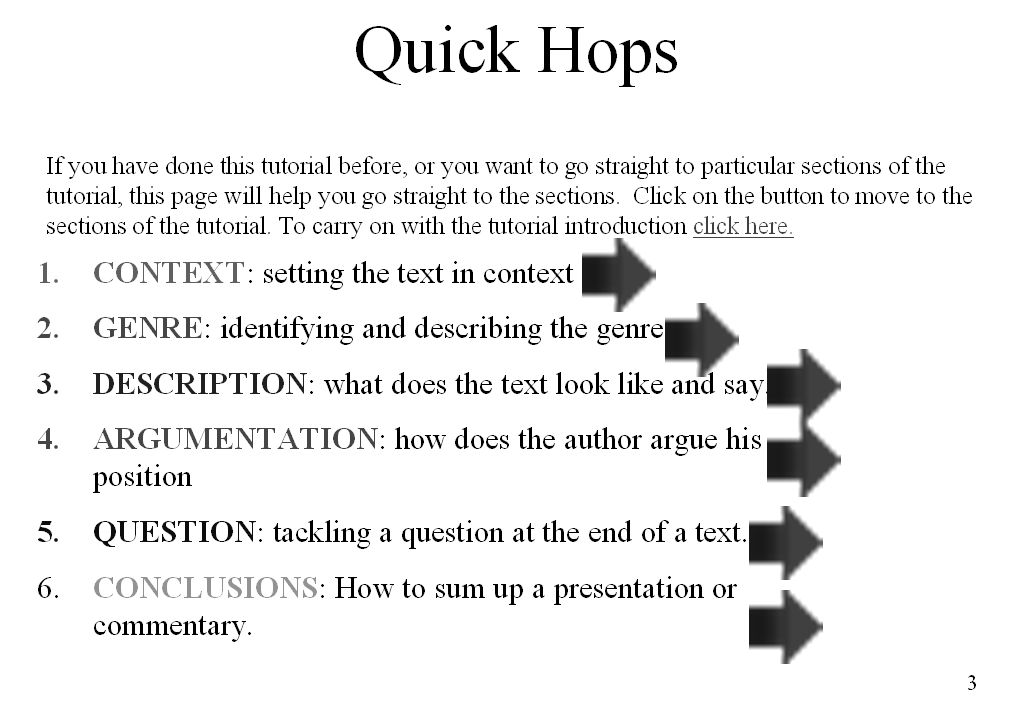

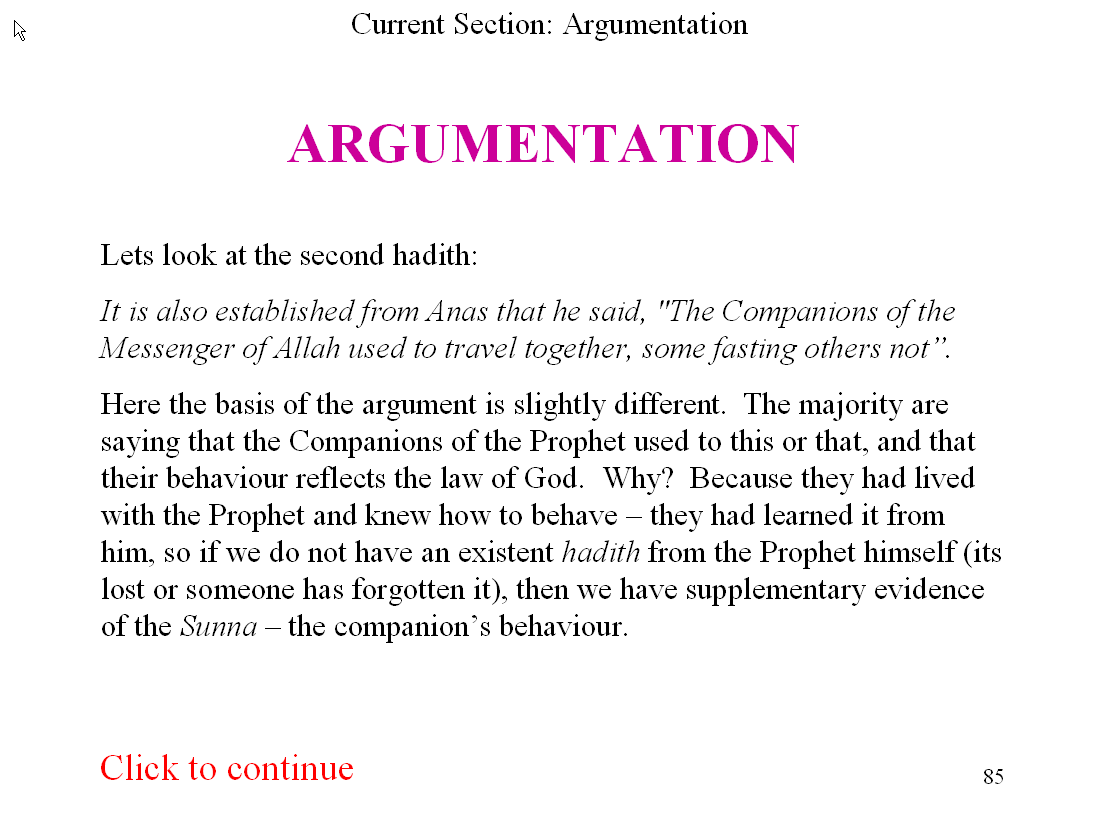

The tutorials were aimed at training students in skills which were an essential element of the unit in question. The most heavily used tutorial was designed to train students in the analysis of classical Muslim texts.13 Through following the instructions in a series of 118 slides,14 students acquired skills in genre recognition, contextualising sources, describing text context, recognising elements of an author's argumentation and use of sources. These skills were developed through reference to a specific 'test text' which the students had access to through a work pack given out in class.

Example slides taken from the PowerPoint tutorial: 'Analysing a Muslim Text'

Figure 1:

Figure 2:

Figure 3:

Having completed the tutorial, students should then be armed with the skills necessary to carry out their own textual analysis of a classical text and present this analysis in class as part of a seminar paper. Textual analysis also formed part of the summative assessment for the unit, as a compulsory examination question involved the analysis of a text (or texts). Through the tutorial, I was aiming to develop skills numbers 1, 2, 4, 5 and 6 listed in the table above.

I had used something similar to this tutorial for a number of years, and I had felt it worked quite well in my classes on Classical Islamic Thought and Islamic Law. In these classes, students are faced with complex and demanding texts which are written in a dense style. The texts were written for specialists, and in order to understand them one must also become, to an extent, a specialist. Without the tutorial, I was having to explain the meaning of each text in class. With the tutorial, students had made the first step towards reading and understanding the texts themselves. It not only freed classroom time to cover other material, it also enabled more sophisticated seminar discussion. I felt that the tutorial was a useful contribution to the unit materials.

In the feedback sessions after the use of the tutorial, I asked students their reactions to the tutorial. Many said they would have been lost without it, as the texts were just too difficult to understand 'cold'. A number asked the question, 'If I were to analyse a text using a different method (that is, without using the headings of genre, context, description, argumentation etc), would I be penalised?' The students felt that in the tutorial I was describing how a student must do an analysis of a Muslim text if they wish to get a good mark, rather than teaching them how one might go about an analysis of a text. To complement this attitude, there were students who slavishly followed the tutorial headings and contents, afraid of producing any original approaches to the texts. Their commentaries contained little of their own reaction to the text and were more of a perfunctory run through of the different sections than an exploration of what the text might mean.

In order to ensure that students had a chance to develop their own opinions on the content of the texts studied in the unit, I added questions and additional reading to both the tutorial and the texts they were studying in class. The questions were open questions such as 'What is your opinion of X's argument for theological position Y, and is his argument convincing?' or 'If you were to argue for position Y, which of X's arguments would you use and which would you discard?' This helped and student reaction was positive. Presentations began to contain more argued opinions from the students. However, I do recognise that a large part of the presentations was rather mechanically drawn from the skills learned from the PowerPoint tutorial. In future years, it will undoubtedly be necessary to encourage students to use the tutorial as a prompt for their own analysis of a text, and to achieve this purpose, a certain amount of redesigning will be required.

The other type of web-based skills training exercises were PowerPoint tutorials and web pages aimed at developing translation skills for students learning the language of a sacred text and tradition (in this case, Arabic). Here there were a number of exercises which, once again, were purely as aids to enable skill attainment.15 There was no work (formative or summative) associated with these exercises. The material in the exercises included Quranic passages accompanied by sound files to improve students' reading skills, and grammatical exercises. The latter consisted of passages which were the subject of translation classes, and each word of the passage was linked to a reference in the grammar book where the form and grammatical properties of the word are explained, together with a hint. Students were supposed to translate the passage from Arabic into English with the help of the web-based teaching aid. They may not have always needed the references and hints, but when they ran into difficulties, they could click on the word and know where to go in the grammar book to find a description of the relevant grammatical construction for this word described. As tutor I noticed that one result of setting the exercise was an improvement in the quality of the 'rough' translations the students brought to class. Furthermore, the students began to recognise grammatical constructions more quickly and developed the ability to look up elements of grammar and vocabulary they did not know or were unsure about.16

In the feedback session on the use of these exercises, students said they found the grammatical exercises useful. However, they also complained that the hints were too elliptical, that the interface was rather primitive and that they needed more help on how to use the grammar book as an aid in translation. These exercises were prototypes and clearly need major revisions before they will function well within a language class. A similar exercise was designed by a colleague for his Hebrew class.17

The PowerPoint tutorials on Quranic Arabic were considered enjoyable by the students, and they liked listening to the sound files and hearing the Qur'an recited by experts. However, I was less happy with the effect these exercises had on classroom progress. Some completed the exercises and improved their reading skills. However, I do not know if this improvement was due to the exercises or was a natural element of progress on the unit. Those students who were struggling with reading the script did not gain much from the exercises, though they said they found them 'fun'.

In terms of web-based exercises which aim to train (but not assess) students in specific skills, on the basis of the above I would conclude the following:

- Exercises should be designed such that the skills attained are reenforced within the classroom setting as soon as possible after the completion of the exercise.

- Students need to feel an investment in the exercise-that is, they need to see the skills being useful not only within the class (ie for seminar papers and discussion) but also within the assessment for the unit/module more generally.

- Exercises should not give the impression that they contain the 'formula' for a correct answer. Rather they should function as an introduction to the possibilities for analysis and progress opened up by acquiring the skill. In this way originality and innovation on the part of the student will not be stifled.

2. Research and Evaluation Exercises

This category of exercises involves students researching using web-based materials and collating material on which an evaluation and student-authored piece of work is then completed and sent to the tutor. The exercises lead the student, through a series of links, to material on the basis of which they compose an original piece or pieces of work.

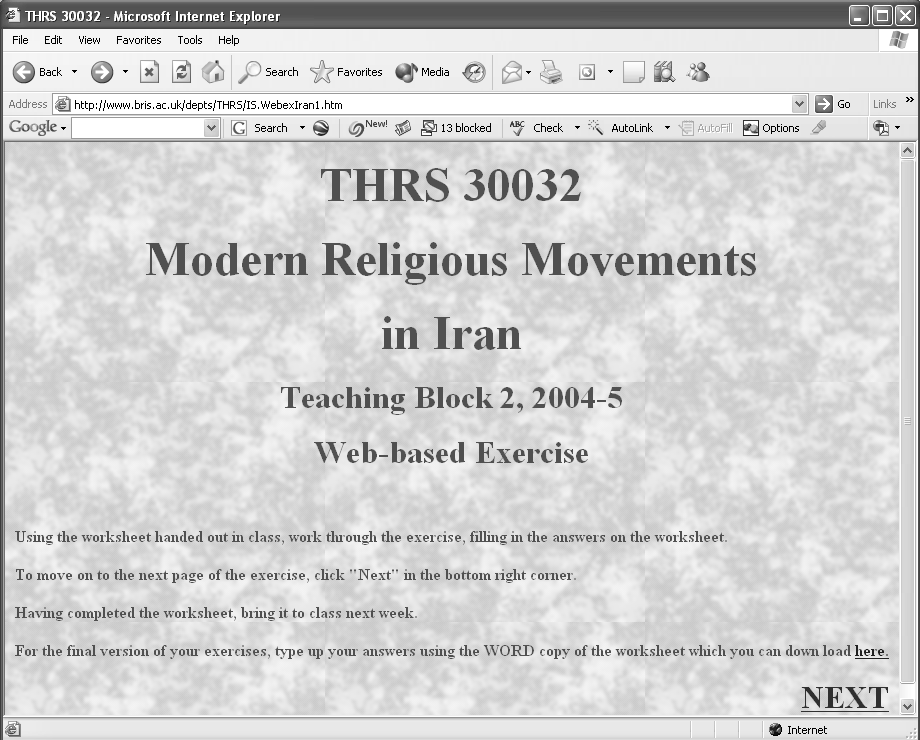

The first of these involved a worksheet, downloaded, completed and printed out by the student.18 The answers to the questions on the worksheet were prose responses of 50 words, answered through reference to web-based materials accessed through a series of web-pages. For example, the students were sent to read two on-line encyclopaedia articles concerning the same topic. The questions asked them to compare and contrast the encyclopaedia articles to identify lacunae in the presentation, emphasis which they might consider appropriate or inappropriate in the entries and the general utility of the articles for a student's research into the subject. The worksheets were printed out and brought to class and formed the basis for discussion in buzz groups which then reported back to the class as a whole.

Figure 6: Page from web-based exercises for the unit Modern Religious Movements in Iran

The feedback from the exercise indicated that whilst the students had gained much from it, they would have appreciated more guidance on how to research and evaluate web-based materials. They were suspicious of web-based materials because, as a department, we have warned them of the pitfalls of using the web as a primary source for essay writing and research. An exercise like this was useful, but, in truth, the skills it assumed in terms of evaluation were insufficiently embedded in the curriculum as a whole. In short, students at the end of their programme of study (these were third year students) found it difficult to distinguish between good and poor quality material on the web: items on the reading list have already been vetted by the module/unit tutor whereas they were required to evaluate the material without being experts in the subject.

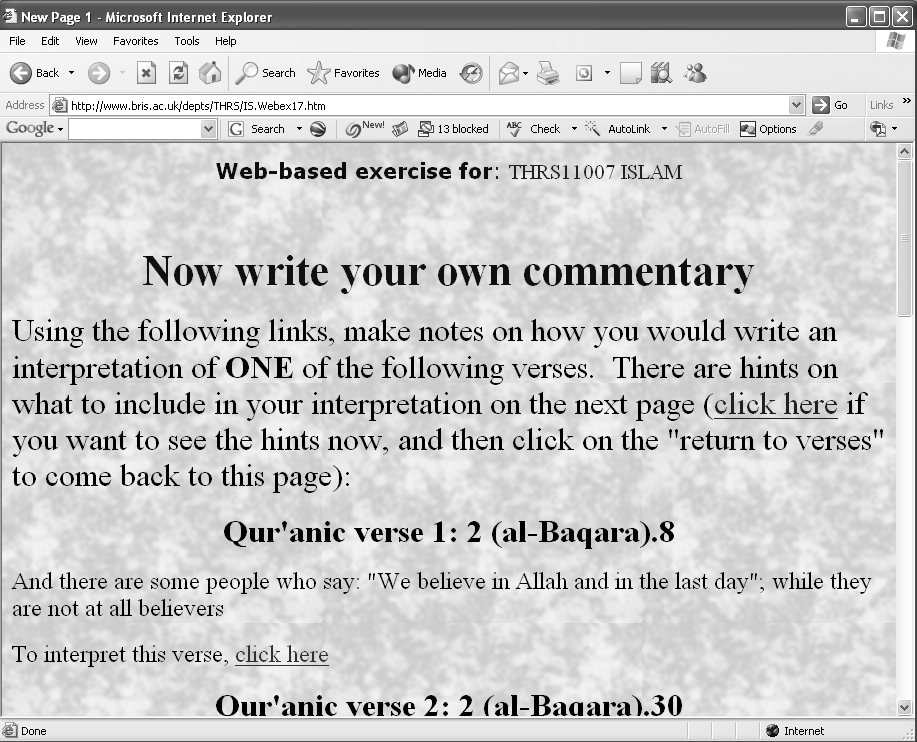

The second exercise in this category aimed to encourage evaluation and composition skills through the study of particular verses of the Qur'an.19 First, an introduction to Muslim techniques of commentary on the Qur'an was presented through a series of web-pages. In particular, the students studied the variety of ways in which a single verse can be interpreted. Students had to select a preferred interpretation, and justify this preference. The justification was submitted to the tutor on a web form, reaching him/her as an e-mail. In the second part of the exercise, students were required to research, through reference to a number of on-line commentaries on the Qur'an, the interpretation of another Qur'anic verse. Having done this, they composed their own interpretation, surveying the interpretations of the verse in the past, and arguing for a particular understanding of the verse. Again, this was sent to the tutor as an e-mail through a web form.

The students found this task more difficult. The responses ranged from bland or frivolous to excellent and detailed. In feedback, they pointed out that the commentaries consisted of difficult and complex passages, and being first year students, they did not feel they had sufficient knowledge to perform the task well. Furthermore, since most were not Muslims, they did not feel they had the 'right' to offer their interpretation of the Qur'an. This last comment, concerning who has the right to interpret scripture, really has nothing to do with the web-based platform for the exercise. It is a fascinating question for a teacher of TRS, but it is not relevant to the evaluation of the success or otherwise of the exercise. The final piece of feedback concerned the submission of an on-line form. This was considered preferable to a printed handout, and students had direct access, by e-mail, to the tutor after the exercise for comments on their answers.

Figure 7: Page shot from web-based exercise on interpreting the Qur'an

On reflection the research and evaluation exercises were only a partial success. Points to consider in designing future exercises include:

- The exercises need to utilise skills already covered elsewhere in the curriculum. That is, the skills need to be attained before they can be developed and employed in a web-based exercise such as the ones trialled here. This was particularly true concerning the evaluation of on-line material.

- Mixing media (ie print media with web-based material) works well for skills training exercises (see above). However, in research and evaluation exercises, where the students are submitting work, it is easier for the students to work within one medium (here, electronic mail and the web) rather than switch between print and screen.

- For formative assessment, the anonymity provided by the web forms (in the second exercise) enabled students to take some risks in the construction of their answers. The responses were subsequently discussed in class, enabling the students to get anonymous feedback. Students who wished for further personalised feedback from the tutor, though, had to identify themselves. This hindered some from seeking this feedback, even though the exercise was purely formative.

3. Comprehension Exercises

The three exercises in this category involved answering specific questions in response to a particular external source. The questions were more often than not 'factual' rather than evaluative, testing students' background understanding of the subject matter as well as how carefully they had studied the external source. Two involved reading sections of an academic article and providing answers to set questions through a web-form.20 The last (not in Islamic Studies) involved answering questions on a web-form after the viewing of a film in class.21

The exercises sprang from a perception amongst departmental staff that students were finding it difficult to study difficult primary and secondary sources carefully. These sources may be advanced and technical articles, or they may be in other media. In order to encourage and develop this close reading of sources, the exercises asked questions which were relatively easy to answer if the student had 'read' the source carefully. There were no tricks, and few evaluative elements. The skills developed and assessed in the exercises were primarily comprehension and analysis. As a package the exercises developed and assessed skills 1 (though with less emphasis on evaluation), 3, 5 (though with less emphasis on reflection) and 6 outlined in the table above.

There were some technical problems with the operation of these exercises. If the student had missed the film in class, the exercise would be meaningless unless they had access to it out of class time. In the case of the exercises based on academic articles, the copyright restrictions on electronic media meant that students faced difficulty accessing the articles off-site (on-site university access was more easily achieved).

Figure 8: Page shot from the web-based exercise interpreting the political theory of Ayatallah Khomeini.

[image missing]

In spite of these, the student feedback was generally positive. The exercises highlighted how infrequently our students read one source carefully. The students found the exercise hard because they would normally 'skip through' an article, looking for relevant sections, rather than read the article as a whole to gain an author's overall argument. They become adept at this 'skim reading', and can construct excellent essays on the basis of this type of reading. Skim reading is an extremely valuable skill for a student, when performed well. It should not be belittled by those of us with the time and inclination to read all the sources carefully. Looking at a piece of writing, and picking out the elements relevant for one's own aims, is a 'key skill' which will be used regularly in the world of work. Many academics have themselves developed and honed this ability. These exercises, however, require a re-focussing of the reader's attention to a single source, read (or watched) carefully in order to gain information demanded by another, rather than information relevant to one's own aims and objectives. It is, perhaps, unsurprising that students found it quite difficult.

Another interesting element of the feedback from these exercises involved the ability (or lack of it) of students to do this kind of close reading on screen. Most students eventually printed out the articles in full, and only then filled in the relevant web-forms. They did not read the source on-line. This may mitigate some of the conclusions reached in the evaluation of the second category of exercises described above. There, it seemed that mixed media (print and electronic) was a hindrance to the students completing the exercise. Here it seemed the main means whereby the exercise could be completed.

Finally, the students felt that the skills of close reading of texts cannot be carried out entirely electronically. By this they not only meant that mixed media was necessary, but that there must be classroom preparation and follow-up to the close reading of complex texts. Without this, the exercise is insufficiently embedded in the curriculum.

The conclusions from the evaluation of the comprehension exercises can be summarised thus:

- The exercises may demand skills which the students rarely use themselves. They have grown accustomed to skim reading and the speedy acquisition of information. An exercise which develops skills of close reading needs to be designed with due consideration given to the difficulty of reactivating this skill in the students.

- The skills of close reading required by comprehension exercises may mean that a mixed media environment functions best-as print and electronic (or film and electronic) are blended.

- The skills of comprehension, employed in the close reading (or watching) of sources, cannot be divorced from the curriculum of a unit/module, or indeed a programme. They are not skills students can attain without reference to a broader learning experience.

Conclusions

In the course of the project I designed 22 web-based learning exercises, trialling them with students, with a view to developing the skills laid down in the Benchmark Statement. In general I witnessed skills progression in the students on completion of the exercises, and this was confirmed in the feedback sessions. The seminar presentations improved and in language classes, student reading skills also improved. Similarly, the essays I received on completion of the unit showed some progress in the close analysis of specific texts and the development of evaluative skills in the assessment of sources. Of course I cannot say how many of these skills would have been developed without the exercises. That is, merely by progressing through a degree programme, students develop and hone skills. Whether or not the exercises were crucial to this progression is unknowable. Student feedback, however, did indicate that the students felt that their skills levels had progressed as a direct result of the exercises.

I did, however, learn a number of important lessons along the way concerning the design and development of the exercises. Firstly, it is clear that the exercises cannot be seen as a substitute for classroom teaching.22 Students at universities (or at least students at my university) want class contact with tutors. Web exercises need to be incorporated into this contact forum, and cannot exist separate from it. Sometimes the skills assessed by the exercises need to be developed within the curriculum as a whole. At other times an exercise needs to be introduced in detail before the student's completion of it, and be followed by extensive feedback sessions on student performance, both individually and as a cohort. In short, web-based exercises can, if designed well and carefully integrated into the curriculum of a particular unit/module, ensure the attainment of a number of the skills laid out in the Benchmark Statement for TRS.23

However, tutors should not see them as a possible avenue for reducing their workload (they do not, believe me), nor should they see them as a simple way of fulfilling benchmark requirements. A unit/module which did not use web-based materials cannot simply have these exercises tacked on to satiate the demands of quality assurance. In my experience, the unit/module has to be redesigned with these exercises in mind, and this, unsurprisingly, requires thought and consideration on the part of the tutor.

Endnotes

- http://www.qaa.ac.uk/academicinfrastructure/benchmark/default.asp

- http://www.qaa.ac.uk/academicinfrastructure/benchmark/ honours/theology.asp (Introduction)

- http://www.qaa.ac.uk/academicinfrastructure/benchmark/ honours/theology.asp (Subject Benchmark Statements)

- http://www.qaa.ac.uk/academicinfrastructure/benchmark/ honours/theology.asp (Knowledge and Understanding)

- http://www.qaa.ac.uk/academicinfrastructure/benchmark/ honours/theology.asp (Knowledge and Understanding)

- Now the Subject Centre for Philosophical and Religious Studies (SC-PRS)

- All these skills are cited in the Subject Benchmark Statement for Theology and Religious Studies. See, http://www.qaa.ac.uk/crntwork/benchmark/theology.html (Indicative statements of threshold and focal levels of achievement in Theology and Religious Studies)

- The numbering of skills is my own, and is for ease of reference later on in this article.

- Whilst the drafters of the Statement include this in the section 'Knowledge and Understanding', it seems clear to me that this is a skill-perhaps generic, perhaps subject specific. To 'be able to evaluate and critically analyse a diversity of primary and secondary sources, including materials from different disciplines' is an ability (surely?) not a piece of knowledge or understanding. It could be argued that we should measure the student's ability to understand primary and secondary sources, but such an ability is not (necessarily) subject specific. An ability 'to evaluate and critically analyse a diversity of primary and secondary sources' is a skill; what the student gains from using that ability is understanding. This is why I have included it as one of the 'skills' covered by the exercises in the Project.

- 'Units' is the University of Bristol term for what most people call 'modules' and 'courses'. Modules and courses do not exist at the University of Bristol.

- I benefited from some of the references found in recent literature on teaching Theology with technology. The main sources are referenced in L. Mercadante, 'High Tech or High Touch: Will Technology Help or Hurt Our Teaching?' Teaching Theology and Religion, 5.1 (2002), p.56 and more recently, S. Delamarter, 'A Typology of the Use of Technology in Theological Education' Teaching Theology and Religion, 7.3 (2004), pp.134-140.

- On blended learning approaches, see J. Seaman, 'Is blending in your future?' Sloan-C View, Vol.3.2 (2003), p.3.

- http://www.bris.ac.uk/depts/THRS/IS.MuslimText.ppt

- See Figures 1, 2 and 3, for examples taken from the PowerPoint tutorial.

- http://www.bris.ac.uk/depts/THRS/IS.ArabicGate.htm

- See figures 4 and 5.

- http://www.bris.ac.uk/depts/THRS/JS.Hebrew1.htm

- http://www.bris.ac.uk/depts/THRS/IS.WebexIran1.htm and see figure 6.

- http://www.bris.ac.uk/depts/THRS/IS.Webex1.htm and see figure 7.

- http://www.bris.ac.uk/depts/THRS/IS.WebexR&Rintro.htm and http://www.bris.ac.uk/depts/THRS/IS.WebexIranintro.htm and figure 8.

- http://www.bris.ac.uk/depts/THRS/useandabuse.htm

- For similar conclusions, see Jill Sweeney, Tom O'Donoghue and Clive Whitehead 'Traditional face-to-face and web-based tutorials: a study of university students' perspectives on the roles of tutorial participants' Teaching in Higher Education vol.9.3, (July 2004), pp.311-323.

- For comparison, see Kim McShane, 'Integrating face-to-face and online teaching: academics' role concept and teaching choices' Teaching in Higher Education vol.9.1, (July 2004), pp.3-16.

Return to vol. 5 no. 1 index page

This page was originally on the website of The Subject Centre for Philosophical and Religious Studies. It was transfered here following the closure of the Subject Centre at the end of 2011.