Teaching and Learning > DISCOURSE

Spiritual Journey Board Game

Author: Aru Narayanasamy and Melanie Jay Narayanasamy

Journal Title: Discourse

ISSN: 1741-4164

ISSN-L: 1741-4164

Volume: 9

Number: 2

Start page: 59

End page: 80

Return to vol. 9 no. 2 index page

Introduction

Spirituality teaching and learning in the context of health care and nursing can be challenging. Traditionally classroom teachings such as lectures, instructions and problem-based learning are all useful strategies that academics can utilise to promote students' understanding of the complex subject of spirituality. Although spirituality is not exclusively about religion and religious needs, some students tend to be dismissive when we explore spirituality because they sometimes associate this concept with religiosity. For some the thought of religion conjures up in their heads images of religion and its alleged ill-effects which for some is counter-productive. There is the concern in health care and nursing that spirituality is under-addressed, with little attention being given to the interior lives of patients, in spite of the evidence that it is associated with patients' narratives about its beneficial effects for their health and well-being. This is not to say that all patients' spiritual needs in health are neglected, as some patients' spiritual needs are met by the staff of the Spiritual and Pastoral Care Departments in hospitals (Cornah, 2006). However, there is empirical evidence to suggest that health care professionals such as nurses may have to initiate actions that best address patients' holistic needs including theirs spiritual needs. My position is that if health care professionals are not able to recognise such needs when assessing the patients' health needs then they are mostly likely to overlook the spiritual care interventions that may be important to patients' lives. Indeed the health care literature shows that health care professionals are unable to address patients' spiritual needs sufficiently due to impoverished educational preparation in this dimension of health care, although its importance is acknowledged among many health care professionals and professional bodies such as Nursing and Midwifery Councils (NMC), the government's health policy directives and other agencies (Narayanasamy, 2006a; McSherry 2007).

As a subject specialist for diversity and spirituality teaching and learning, I have always explored alternative ways of teaching this subject as part of my efforts to create a better learning experience for students. I have tried various methods, ranging from lectures to small group didactic teaching and problem-based learning using clinical scenarios with varying degrees of success. It has been a real challenge to engage the less interested and more sceptical members of my class. The most resistant sceptics have been non-believers and those with antagonistic views towards religions. My concerns were to look for other innovative means to engage individuals with such inclinations. As I reflected and mulled over approaches to spirituality teaching, one early morning I woke with an inspirational idea about a board game as a spiritual journey. Boyle (1997) suggests that educational games are conducive to learning in that they encourage students' engagement as they find such learning delightful and powerful. My idea of an educational game for spirituality teaching must have been implanted in my head by two other factors: first, my experiences with students, and secondly, my encounters with patients:

- In one of the classroom sessions, some students reflected about their spiritual journey in terms of how their interior lives had been shaped by certain milestones in their lives or turning points when they reached a crossroad. It dawned on them that something spiritually was happening and how significant this had been to them in making key decisions in their lives, including their motivation to become health care professionals.

- Some patients hinted to me that they sought comfort and healing through their spirituality including religions, but some found new meanings and purpose, though sometimes not through any recognisable religion or faith (Narayanasamy 2002).

These reflections, and the inspiration I felt on waking up in the early hours of the morning, compelled me to jot down quickly my ideas for the board game. I sketched the plan of the game and drafted some game rules to go with it. My family became the first tester of the prototype game and initial modifications were made to it in the light of their feedback. There then followed several trials of it in my teaching sessions as an introduction to spirituality and spiritual care to nursing students following courses to become registered nurses (RNs). Following each session the effectiveness of the game was evaluated and at the early stages the game's design and rules, were subjected to redrafts and further refinement. The final version of the spiritual journey game is given below.

There is evidence in the pedagogical literature that educational games tend to capture students' interest and engagement with the subject matter of the teaching session far more effectively than other conventional methods of teaching such as lectures and related didactic instructional methods (Boyle 1997). However, there is also the acknowledgement in the literature that educational games should not be a substitute for well tried conventional teaching methods such as instructions, particularly in the health sciences where safety is paramount to the health care and treatment. A recent systematic review on educational games in health sciences draws from several studies to suggest that high levels of knowledge were demonstrated among students exposed to educational games, but it is also inconclusive about the overall effectiveness of such games (Blakely, Shirton, Copper et al. 2009). Furthermore, Jungman (1991) found, in an evaluation study of educational games, that students' responses were positive with indications of motivation, competition and non-threatening features. This evidence gave me the confidence in my approach to teaching spirituality to nursing students and health care practitioners using the spirituality game board. However, I also acknowledge that not all students find games beneficial to their learning experience (Blakely et al. 2009).

The Spiritual Journal Game

This educational game was developed in response to the concern in health care education that despite evidence about the importance of patients' spiritual needs, spiritual care education is impoverished (McSherry 2007; Narayanasamy 2006b). Although conventional teaching strategies including lectures and group sessions have been tried with varying degrees of success in teaching and learning spirituality, the sensitive nature of this subject appears to hinder academics and students' engagement with this topic due to fear of vulnerability and disclosure of personal beliefs and values. This educational board game is proposed as an alternative strategy for the teaching and learning of this complex but important subject.

The light hearted strategy of this educational game aims to inspire participants to gain insights into spirituality in patient care. The learning outcome of this game should improve spiritual care education, therefore benefiting health and well-being. The game draws attention to human potentials and vulnerability in terms of meaning making and purpose, connectedness, hope, love, peace and tranquillity, compassion, caring and so on. Participants should be able to appreciate through the game what caring companionship means to those in suffering when experiencing crisis and vulnerability as a consequence of illness or personal catastrophes.

This educational game sets 2-6 players on a personal spiritual journey to gain insights into how people use spirituality as a coping mechanism in their lives (Narayanasamy 2004). The game will prompt students to explore their own spiritual growth and development. In several trials of this game, nursing students and practitioners, as players, have undertaken the spiritual journey as an introduction to spirituality and well being. The game has been refined following evaluation feedback from game participants.

The game comprises a board, dice, rules and instructions, and facilitator's guidance notes. The game ends when the winner reaches the final destination on the board, which constitutes spiritual fulfilment in terms of spiritual growth and development. At the end of the game, the facilitator will proceed to explore what participants have derived from the game in terms of spiritual awareness in the context of health and well-being.

In the spiritual journey game that I had designed and used in my spirituality introductory session, students are encouraged to play the game to get some insights into spirituality and spiritual needs as a collective learning experience with peers. Throughout the spiritual journey, which takes place on the game board, it subjects the players with opportunities to collect spiritual resources cards which allow them to proceed with the game. The players could use the spiritual resource cards to keep out of spiritual distress and the winner is the one who arrives at the journey's destination which depicts spiritual fulfilment. At this point, the game ends and the discussion on spirituality is then facilitated by the session tutor.

Key features of the game

Before the game begins, the players are given instructions, both verbal and written, about the rudiments of the game and its rules. I have used the game with groups ranging from 6 to 70. In larger groups I have used up to 7 game boards. The players are asked to familiarise themselves with the various features of the games. The key features of the games are as follows.

Spiritual Well-being Centre

For the purpose of the game, the spiritual well-being centre is a virtual one. This centre is there to help spiritually distressed individuals to regain their spiritual strength by attaining meaning and purpose in their lives. The centre has both physical and staff resources to support indi64 Aru Narayanasamy et al—Spiritual Journey Board Game viduals with provisions and space for personal retreat—for example it offers sacred space for those who want to have time for personal contemplations, quiet reflections, meditations and prayers. The centre offers the services of spiritual advisers and therapists for those who request support with their spiritual quest and search.

Players who collect the wild card or 4 spiritual distress cards are required to visit the spiritual well-being centre and stay there until they have made spiritual recovery. In this case, the players who resume the game are those who have had the opportunity to regain meaning and purpose (spiritual well-being) in their lives by accessing the facilities and resources of the centre. Players leave the spiritual well-being centre by rolling a '6' on the dice. If they don't roll a 6 on their first or second go whilst in the spiritual wellbeing centre, then they have to wait for their third go. As they exit from this centre, players take their place in the game by collecting a new beginnings card which indicates the number to locate their position.

Spiritual resource cards

Individual spiritual resource cards indicate spiritual attributes to depict spirituality and spiritual well-being. The more spiritual resource cards that players acquire, the better their state of spiritual well-being. Players can hand in their 4 spiritual resource cards to stay in the game should they get 4 spiritual distress cards. If they are unable to do this, then they are forced to go to the spiritual well-being centre.

At times players may end up with wild cards which normally indicate that they are facing major spiritual crisis in their lives (for example all catastrophes happening at the same time with events such as facing marital/relationship breakdown, being sacked from job and house repossession) and require time at the spiritual resource centre. In this case, if they possess 4 spiritual resource cards, then they may continue to stay in the game by surrendering them with the wild card.

Spiritual distress cards

Each spiritual distress card indicates attributes that are normally considered to generate negative experiences or spiritual distress. Players who have acquired 4 spiritual distress cards indicate that they are facing severe spiritual distress and require time at the spiritual wellbeing centre. If they have do not have 4 spiritual resource cards to trade off the 4 spiritual distress cards, then they are required to spend time at the spiritual well-being centre.

Players can help others to stay in the game by donating spiritual resource cards. For example, they may let displaced players stay in the game by collecting a spiritual resource card from them, if they wish. (A displaced player is somebody who was on a particular spot, but then gets displaced by another player landing in the same spot, see rules).

Players may imaginatively improvise to allow flexibility in the way they treat their opponents, if it is at all possible. We all are companions in the spiritual journey as players constantly face ups and downs in the journey, with some making good progress, while for others the journey is hazardous as life is not straightforward. It is an expectation that players will collaborate and support each other in the journey. The game offers opportunities for self-awareness and reflections on human life, through empathy and insights into how spirituality offers coping mechanisms for individuals to regain some spiritual strength through new meanings and purpose.

Once the players have gone through the journey with the winner attaining spiritual fulfilment, the game ends and the session commences with personal reflections and subsequent discussion as indicated in the resource package that accompanies the board game.

The winner

The winner is the one who has attained spiritual fulfilment by negotiating and navigating through the smooth routes and rough terrains of the journey as part of the game. In attaining spiritual fulfilment the winner is entailed to collect all the spiritual resource cards from the game. At the end of the game all cards can be displayed to participants for personal reflections and discussion. Following the reflections on the game and insights derived, the discussion will focus on the spiritual resources and spiritual distresses to illustrate how spirituality features in people's lives and how this can be an important resource for coping with the challenges of life in health and illness.

Resource package

The resource package comprises the learning material for the session. The facilitator may use the presentation slides, found in the resource package, to introduce the concept of spirituality, spiritual needs, spiritual care and the seven steps of personal spiritual growth and development. The resource package could be used as independent learning material following the game.

Rules of the Spiritual Journey Game

This game entails players making a spiritual journey as part of their spiritual growth and development. Players gain greater awareness of what spirituality means in a light hearted manner by engaging in the game. There are ups and downs throughout the journey in which players make accelerated moves or move backwards several places. As players undertake the journey, they acquire both spiritual resource and spiritual distress cards. The winner is the one who completes the spiritual journey by acquiring spiritual resource cards from the box and other players, to depict that the winner has reached spiritual fulfilment. A reflective discussion starts on spirituality when the game ends.

SR= Spiritual Resource

SD= Spiritual Distress

- 2 to 6 people can play the game.

- Game starts when first one rolls dice with 6 or the next highest number; others follow by throwing any number.

- Players move forward or backwards as per instructions in the card or board.

- If you get 6, you can throw dice again.

- When landed on SR (Spiritual Resource) collect Spiritual Resource Card, make sure all cards are different types in your possession. In most cases, landing on SR allows accelerated moves.

- When landed on SD (Spiritual Distress) you collect Spiritual Distress Card and in some instances you may be directed to go the spiritual well-being centre. See rule 7 how to get back into the game.

- If a player acquires four spiritual distress cards, they move to the Spiritual Well-Being Centre for recovery and wait for their turn. The player waiting at this centre can only move by rolling 6 or on their third go. To join the game this player then picks a new beginnings card and takes position according to allocated number by returning 4 SD (Spiritual Distress) cards.

- If someone lands on your position, you need to wait in the Spiritual Well-Being Centre, and join the gain game when you roll 6. At this point, you pick a new beginnings card and take position in the game according to the allocated number. (NB: the player who lands in your position has the option to allow you to stay in the game by accepting a spiritual resource card from you).

- The game ends when the first one arrives at the finish point (100=Spiritual Fulfilment), and requires the exact number at the last stop to reach the finish point. For example, if you were on the '97' space, you can only roll a '3' to reach 100 or a '2' or a '1' to get closer; a '4' would not be accepted.

- If you pick wild cards from the spiritual resource pack, this means that you had a spiritual crisis. You then proceed to the Spiritual Well-Being Centre to recover.

- The winner achieves Spiritual Fulfilment, collects all SR cards from box and reads out the contents of the spiritual resource cards.

- The runner-up and others read out the contents of the spiritual distress cards.

- The facilitator leads the discussion on spirituality in the light of what insights participants have gained from the game, with regards to spiritual resources and spiritual distress. Facilitator resource package is used for all the sessions.

Dynamics of the game

The game is interactive and the players experience fun and frustrations. Players may collect spiritual resource cards and progress or collect spiritual distress cards and face delay in their journey. They can also land themselves at the spiritual well-being centre when they get a wild card with indications of extreme spiritual distress inflicted upon them. Moreover, the game offers opportunities for players to display empathy and altruistic gestures to their fellow travellers.

Reflections

At the end of the game, participants are asked to reflect about what they had derived from the game as follows: Take a moment to reflect on the spiritual journey you have undertaken. What insights have you gained from this game? You can look at the spiritual resource cards to aid your reflections. Jot down in the box below your reflections.

Examples of reflective points arising from students reflections:

- I thought the game was successful in showing that life can be shaken unpredictably and that spirituality can aid us in coping.

- I liked the game.

- It was a good idea and enjoyable but I would have preferred it to be accompanied by more practical, useful information about spirituality and nursing.

- Good fun, we wish we had longer to play.

- I loved the game, it helped me to understand spirituality, and my own spirituality as well.

- I love the game, you're welcome to do similar sessions for us.

- It was an interesting session which made the learning fun.

- It was fun, it aided learning in a relaxed environment, thanks.

The ASSET model

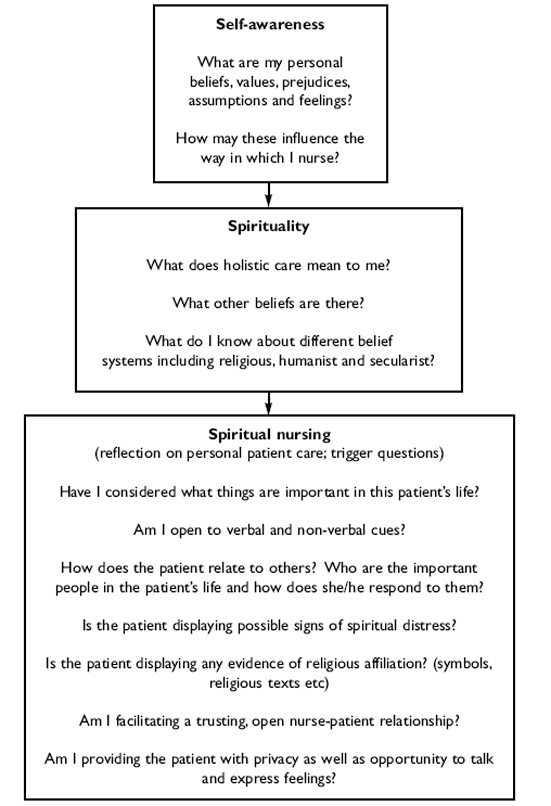

Following the discussion on the personal reflections about the game experience, there then follows a discussion on what we mean by spirituality and spiritual needs in the context of health care. The facilitator may use the teaching and learning package derived from the ASSET Model (Narayanasamy 2006b) that accompanies the game. I developed it as a framework for teaching spirituality in nurse education; to develop the reflections and discussions on spirituality and personal self-awareness. A CD comprising presentation slides as per details given below may used to support the session.

Structure for the lesson (slides provided)

The following structure was used to develop the lesson.

What is spirituality?

Spirituality is considered to be 'the essence of our being and it gives meaning and purpose to our existence' (Narayanasamy 2006a). Our spirituality gives us a sense of personhood and individuality. It is the guiding force that gives us our uniqueness and acts as an inner source of power and energy, which makes us 'tick over' as people. Spirituality is the inner, intangible dimension that motivates us to be connected with others and our surroundings. It drives us to search for meaning and purpose, and establish positive and trusting relationship with others. There is a mysterious nature to our spirituality and it gives peace and tranquillity through our relationship with 'something other' or things we value as supreme.

Our spirituality sets us on a journey as part of our growth and development. It provides us with a sense of wholeness, stability, wellness, security, hope and peace. Spirituality can be an important source of wisdom, inspiration, meaning and purpose. According to Coyle (2002), spirituality 'motivates, enables, empowers, and provides hope'. It comes into focus at critical junctures in our lives when we face emotional stress, physical illness or death.

Religion

For most of us the word 'religion' tends to create images in our minds of external things like buildings, religious officials and public rituals, such as baptisms, weddings, and funerals. For some individuals these are times when they come into contact with something to do with religion, with or without a deeper religious significance. Some people may be highly spiritual in nature but are not necessarily religious and others may be religious without being spiritual. Whilst some people may use religion as a medium to express their spirituality and as a way of relating to the transcendent (MacKinlay 2001), spirituality is more of a journey and religion may become the transport to help us in our journey.

Although there is evidence to suggest that membership of established 'mainstream churches' has dropped dramatically it is now esti- mated that there may be many new religious groups in the United Kingdom (Brierley 2000). This may be due to the spiritual void that many people may be experiencing. The spiritual need for searching for meaning and purpose may act as intangible motivators for membership of New Religious Movements (NRMs).

Spiritual needs

Spiritual needs may be attained through meaning and purpose, loving and harmonious relationships, forgiveness, hope and strength, trust and personal beliefs and values, spiritual practices, concept of God/Deity, beliefs and practices, and creativity.

The search for meaning and purpose

- Finding meaning and purpose

- Finding meaning and purpose in illness and suffering

- Searching and seeking motivation as to why and how to live

Sources: Coyle (2002); Narayanasamy (2006b)

Love and harmonious relationships

- A universal need, especially love that is unconditional (no strings attached to it)

- Relationships with people, living harmoniously with people and their surroundings

- Deriving inner peace and security from love and harmonious relationships

Sources: O'Brien (2003); Narayanasamy (2006b)

Forgiveness

- Guilt is a universal human phenomenon that needs to be overridden by forgiveness

- Believers may seek forgiveness through their faith/religion; however, non-believers may not have such opportunities but still need to find the means to be forgiven

Sources: Narayanasamy (2006b; Macaskill 2002)

Hope and strength

- Sources, religious or spiritual, that gives hope and strength to go on living and face challenges of life

Sources: Benson and Stark (1996); Thomsen (1998); Narayanasamy (2001); Koenig (2001).

Trust

- Emotional and physical security

- Stable environment and living give security and peace

Source: Narayanasamy (2006b)

Personal beliefs and values

- Life principles and values

- Religious and cultural beliefs

- Humanistic needs

Source: Narayanasamy (2006b); O'Brien (2003)

Spiritual care

A problem based approach may be used systematically to plan care to meet the spiritual needs of their patients. Helping patients in their growth can lead to improvements in patients' overall well-being. There is the emphasis in the literature that the primary purpose of spiritual care is to help the person suffering from sickness or disability to attain or maintain peace of mind. The following steps may be used for spiritual care.

Assessment

Valuable information central to spiritual needs should be obtained from patients. The following Spiritual Assessment Guide may help with the gathering of such information (see table below).

| Needs | Questions | Assessment Notes |

| Meaning and Purpose | What gives you a sense of meaning and purpose? Is there anything especially meaningful to you now? Does the patient/client make any sense of illness/suffering? Does the patient/client show any sense of meaning and purpose? | |

| Sources of Strength and Hope | Who is the most important person to you? To whom would you turn to when you need help? Is there anyone we can contact? In what ways do they help? What is your source of strength and hope? What helps you the most when you feel afraid or need special help? | |

| Love and Relatedness | How does patient relate to: Family & relatives; Friends; Others; Surrounding. Does patient/client appear peaceful? What gives patient/client peace? | |

| Self Esteem | Describe the state of client/patient's self esteem How does patient/client feel about self? | |

| Fear and Anxiety | Is patient/client fearful/anxious about anything? Is there anything that alleviates fear/anxiety? | |

| Anger | Is patient/client angry about anything? How does patient/client cope with anger? How does patient/client control this? | |

| Relation between spiritual beliefs and health | What has bothered you most being sick (or in what is happening to you?) What do you think is going to happen to you? |

Planning

The information from the application of above assessment guide may contribute to the formulation of spiritual care plans. When formulating the care plan, careful consideration should be given to the patient's individuality, the willingness of the nurse to get involved in the spirituality of the patient, the use of the therapeutic self, and the nurturing of the inner person (the spirit).

Implementation (Giving spiritual care)

Implementation is about spiritual care intervention based on an action plan which reflects caring for individual. It is necessary to develop a caring relationship which signifies to the person that he or she is significant. It requires an approach which combines support and assistance in growing spiritually. In order to implement spiritual care the following skills are necessary: Self-Awareness, Communication; Trust Building and Giving Hope (Narayanasamy 2001; McSherry 2000).

Evaluation

As part of evaluation, the following questions may be helpful:

- Is the patient's belief system strong?

- Do the patient's professed beliefs support and direct actions and words?

- Does the patient gain peace and strength from spiritual resources (such as prayer and minister's visits) to face the rigours of treatment, rehabilitation, or peaceful death?

- Does the patient seem more in control and have a clearer self-concept?

- Is the patient at ease in being alone? In having life plans changed?

- Is the patient's behaviour appropriate to the occasion?

- Has reconciliation of any differences taken place between the patient and others?

- Are mutual respect and love obvious in the patient's relationships with others?

- Are there any signs of physical improvement?

- Is there an improved rapport with other patients?

Seven Steps to Spiritual Growth and Development

Following the above presentation and discussion about spirituality and spiritual care in health practice, the facilitator may introduce participants to the seven steps to spirituality growth and development as way of helping them to become aware of their own spirituality. The Seven Steps offer strategies for participants to develop personal resources to enhance their spiritual well-being.

The Seven Steps will help you with your spiritual growth and development.

Step One: Positive Self Concept

- Consider yourself to be unique, rich in personality with diverse interests and qualities.

- Love yourself.

- Possess a positive self-looking glass: develop a positive self-image and self-esteem.

- Be generous in saying positive things about others, these will be reciprocated which in turn will be good for your self concept.

- Treat contradictions about yourself as unreal.

- The media creates false images and a totally unreal world around us. Do not let media illusions influence you.

Step Two: Self Awareness

- • Appreciate your humanness.

- • As part of your humanity you have strengths and weaknesses.

- • You are not a superhuman, sometimes you are allowed to get things wrong.

- • If things go wrong, do not put yourself down. We all make mistakes but some of us are good at covering them up.

- • Recognise your strengths and weaknesses.

- • Learn by your mistakes.

- • Learn to be open and sincere. People will respect you for this.

Step Three: Meaningfulness and purpose

- Appreciate everything and every minute of your life.

- Be thankful of all your qualities as a person, with a body, mind and spirit.

- Nature/ your maker (whatever your beliefs are) created you to be a unique person of bright colour in the rich tapestry of life.

- Try to bring meaning to what you do, work, leisure, home etc.

- Accept that sometimes things can be meaningless and purposeless, but they never last. There is hope and work towards achieving meaning and purpose.

Step Four: Inner Peace and Be a Peace Maker

- Do everything possible to attain inner peace.

- Be contented with what you are by appreciating your uniqueness.

- Anger is destructive to self and others. There are no gains in being angry.

- Be a peace-maker

- Be the first person to make peace.

- Resolve conflicts at the earliest opportunity

- A peaceful person is always in control and generates a peaceful environment.

Step Five: Connectedness

- Be in tune with yourself.

- Seek opportunities to remain connected with others (family, friends) and your surroundings.

- If you are a believer, remain in touch with your God/Deity.

Step Six: Forgiveness

- Always forgive yourself and others.

- Self-blame and guilt feelings will only hurt you, not others, so why blame yourself?

- Resolve conflicts

- If you cannot easily forgive, learn to forgive, for example, writing it down.

- Putting thoughts/expressing feelings into writing may provide the emotional catharsis.

Step Seven: Create Space and Time for your Self

- Create a space in your accommodation, which you can call a personal/sacred space for yourself. A place where you can go and meditate/reflect undisturbed.

- Let others know you need time to be in your sacred space.

- Meditate or do relaxation exercises or pray, if you can. Do this regularly, and see results.

Conclusion

This game and its trials demonstrate how a small idea can be nurtured and translated into a potential resource for the teaching and learning of complex subjects such as spirituality, especially as a means to engage sceptical and antagonistic students with misconceptions. As in the case of any educational game, teaching may evoke unpredictable reactions affecting the educational milieu that may be detrimental to learning. As a consequence teachers may face challenges as how best to salvage the situation that is detrimental to learning. Educational games such as this offer opportunities to create desirable conditions, where mutual respect, sensitivity and understanding are required, to promote student engagement and tolerance to diverse and contentious opinions that may occur when the intricacies of spirituality and spiritual needs are explored.

I have conducted several sessions so far, and apart from earlier teething problems with the game rules, this education game is proving to be popular with students. The students' qualitative feedback from the earlier sessions helped to refine the rules to eliminate ambiguity related to some areas. The refinement has rendered the game as a useful resource for teaching spirituality to both students and experienced health care practitioners returning to pursue with learning beyond registration courses. It is acknowledged that the teaching using this game is evolving and each spirituality session can be unique because sometimes spirituality evokes unpredictable reactions and it is the teacher and not the game who has the responsibility to address the class in a mutual and compassionate manner. Although students' qualitative feedback indicates largely positive comments, it is my intention to conduct evaluation studies of this game using quantitative measures to produce statistical evidence about its usefulness as teaching tool. It transpired from later sessions that this game could be adapted for teaching religious and ethical studies and leadership courses where the emphasis is in creating organisational well being, a recurrent theme in the current climate of fiscal retrenchment. I will be exploring opportunities to work with colleagues from these subject areas to adapt the game for their purposes as it has great potential as a teaching and learning resource.

References

Benson, H; Stark, M., Timeless Healing: Power and Biology of Belief, (London: Simon and Schuster, 1996).

Blakely, G, Skirton, H, Cooper, S, Allum, P, Nelmer, P. 'Educational Gaming in the health sciences: systematic review', Journal of Advanced Nursing, 65 (2), 2009, pp. 259-269.

Boyle, T., Design for Multimedia Learning, (Prentice Hall: London, 1997).

Brierley, P. (ed) Religious Trends 2000, (London: Harper Collins, 2000).

Cornah, Debrah, The Impact of Spirituality on Mental Health. A Review of the Literature, (London: Mental Health Foundation, 2006).

Coyle, J., 'Spirituality and Health: Towards a Framework for Exploring the Relationship Between Spirituality and Health', Journal of Advanced Nursing 37(6), (2002) pp. 589-597.

Jungman, S.I., 'The Effect of the Game Anatomania on Achievement of Nursing Students', Thesis, (Drake University: USA, 1991).

Koenig, H. G., Spirituality in Patient Care: Why, How, When and What?, (Radnor, Pennsylvania: Templeton Foundation Press, 2001).

Macaskill, A., Heal the hurt. How to Forgive and Move On, (London: Sheldon Press, 2002).

MacKinlay, E., The Spiritual Dimensions of Ageing, (London: Jessica Kingsley, 2001).

McSherry, W., Making Sense of Spirituality in Nursing Practice, (Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2000).

McSherry, W., The Meaning of Spirituality and Spiritual Care within Nursing and Healthcare Practice: a Study of the Perceptions of Health Care Professionals, Patients and the Public, (London: Quay Books, 2007).

Narayanasamy, A., Spiritual Care: A Practical Guide for Nurses and Health Care Practitioners, 2nd Edition, (London: Quay, 2001).

Narayanasamy, A., 'Spiritual Coping Mechanisms in Chronically Ill Patients', British Journal of Nursing 11, (2002) pp.1461- 1470.

Narayanasamy, A., 'The Puzzle of Spirituality for Nursing; a Guide to Practice Assessment', British Journal of Nursing 13 (19), (2004) pp.1140-1144.

Narayanasamy, A., 'The Impact of Empirical Studies of Spirituality and Culture on Nurse Education', Journal of Clinical Nursing 15, (2006a) pp. 1-12.

Narayanasamy, A., Spiritual and Transcultural Health Care Research, (London: Quay, 2006b).

O`Brien, M.E., Spirituality in Nursing: Standing on Holy Ground, (Boston: Jones and Bartlett, 2003).

Thomsen, R., 'Spirituality in Medical Practice', Archives Dermatology 134(11), (1998) pp. 1443-1446.

Return to vol. 9 no. 2 index page

This page was originally on the website of The Subject Centre for Philosophical and Religious Studies. It was transfered here following the closure of the Subject Centre at the end of 2011.